Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Mitigation, Resilience, and Environmental Management: A Review of Algorithmic and Equity-Focused Prioritization under Uncertainty

| Received 08 Oct, 2025 |

Accepted 20 Jan, 2026 |

Published 31 Mar, 2026 |

Nature-based solutions (NbS) leverage ecological processes to address climate change while providing biodiversity conservation and human well-being benefits. This review synthesizes the conceptual foundations of NbS, evaluates their climate mitigation and resilience potential, and examines governance, equity, and research priorities for operationalization at scale. Evidence for carbon sequestration across forests, wetlands, peatlands, mangroves, and soils highlights NbS as cost-effective contributors to near-term mitigation with co-benefits including habitat restoration, water regulation, disaster risk reduction, urban heat mitigation, and livelihood support. Key challenges such as scalability, monitoring gaps, policy misalignments, and risks from single-metric prioritization are identified. Decision-support methods including multi-criteria analysis, GIS-based spatial optimization, multi-objective evolutionary algorithms, and machine learning enable scenario simulation and tradeoff quantification among carbon, biodiversity, and adaptation outcomes. Integrating uncertainty through ensemble analysis, sensitivity testing, and robust decision-making is crucial for risk-aware planning. Equity and justice considerations emphasize inclusive governance, indigenous stewardship, free prior informed consent, and targeted finance mechanisms. The review concludes by proposing a research and practice roadmap that promotes algorithmic fairness, co-optimization of social and ecological objectives, sustainable finance innovation, and transdisciplinary collaboration to ensure NbS deliver effective, equitable, and resilient outcomes.

| Copyright © 2026 Anih et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Climate change continues to intensify as one of the defining crises of the 21st century, manifesting through rising global temperatures, biodiversity loss, sea-level rise, and increasingly frequent extreme weather events. These impacts threaten not only ecological integrity but also human health, food security, and economic stability, particularly in vulnerable regions. Against this backdrop, nature-based solutions (NbS) have emerged as a critical paradigm for addressing climate challenges by leveraging ecological processes to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, enhance resilience, and deliver co-benefits for biodiversity and human well-being1. Unlike conventional engineered interventions, NbS provide multifunctional outcomes, such as carbon sequestration, flood regulation, and livelihood support, making them central to both climate adaptation and mitigation strategies2.

The rationale for integrating climate mitigation, resilience, and environmental management through NbS lies in their ability to address multiple objectives simultaneously. For example, reforestation projects not only capture atmospheric carbon but also restore degraded habitats, regulate hydrological cycles, and improve soil fertility3. Similarly, coastal mangrove restoration reduces storm surge risks while sustaining fisheries and protecting biodiversity. This multifunctionality positions NbS as a cornerstone of global sustainability agendas, including the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals, where synergistic solutions are increasingly prioritized over siloed interventions4.

However, as the scale and complexity of NbS initiatives expand, prioritization under uncertainty has become a pressing challenge. Climate projections, socio-economic pathways, and ecological responses are inherently uncertain, complicating decisions about where, when, and how to implement NbS. To address this, algorithmic approaches ranging from multi-criteria decision analysis to machine learning and spatial optimization are being applied to systematically evaluate trade-offs and identify robust strategies5. These computational tools enable planners to integrate diverse datasets, simulate future scenarios, and optimize NbS portfolios under varying conditions, thereby enhancing decision-making capacity in the face of uncertainty.

Yet, the rise of algorithmic approaches also underscores the importance of embedding equity and justice in NbS planning. Without deliberate attention to distributional, procedural, and recognitional equity, NbS risks reproducing or even exacerbating existing inequalities. For instance, projects that prioritize carbon sequestration without considering local land rights may marginalize indigenous communities or shift burdens onto vulnerable groups6. Embedding equity ensures that NbS not only deliver ecological benefits but also advance social justice, inclusivity, and long-term legitimacy.

The objective of this review is therefore to synthesize current knowledge on NbS, with a particular focus on their conceptual foundations, algorithmic prioritization under uncertainty, governance frameworks, and equity considerations. By integrating insights from ecological science, computational modeling, and social justice scholarship, this work aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how NbS can be designed and implemented to maximize climate, biodiversity, and societal benefits in an uncertain future7.

CONCEPTUAL FOUNDATIONS OF NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

This section provides a concise synthesis of how nature-based solutions have evolved from the ecosystem services concept into a coherent policy framework, compares definitions and priorities from the IUCN, IPCC, and UNFCCC, and explains how these approaches connect adaptation, mitigation, and resilience. It summarizes the carbon sequestration potential of forests, wetlands, peatlands, mangroves, and soils, contrasts nature-based solutions with engineered options such as carbon capture and storage, and demonstrates how NbS can deliver substantial, cost-effective mitigation alongside multiple co-benefits.

The study also highlights biodiversity, water regulation, disaster risk reduction, and livelihood benefits, while clearly addressing practical challenges around scalability, monitoring and verification, the risk of greenwashing, and the imperative to embed equity and inclusive governance.

Defining nature-based solutions (NbS) evolution of the concept: From ecosystem services to NbS: The concept of nature-based solutions (NbS) has evolved significantly over the past two decades. Initially, the focus was on ecosystem services, which emphasized the direct and indirect benefits humans derive from ecosystems, such as clean water, pollination, and climate regulation. However, as global environmental challenges intensified, the framing shifted toward NbS, which emphasizes practical, scalable interventions that harness natural processes to address societal challenges. This transition reflects a broader recognition that ecosystems are not only service providers but also active agents in climate adaptation, mitigation, and resilience building. Recent scholarship highlights that NbS emerged as an umbrella concept integrating ecosystem-based adaptation, ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction, and green infrastructure into a unified framework for sustainability policy and practice7.

Global frameworks (IUCN, IPCC, UNFCCC) and their interpretations: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has been central in formalizing NbS definitions. Its Global Standard for NbS defines them as “Actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, while simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits”8.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has incorporated NbS into its assessment reports, framing them as critical pathways for achieving climate mitigation and adaptation goals. The IPCC emphasizes that NbS can deliver synergistic benefits by reducing greenhouse gas emissions while enhancing biodiversity and human resilience.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) recognizes NbS as essential for achieving the Paris Agreement targets. The NbS are increasingly integrated into Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), with countries pledging large-scale reforestation, wetland restoration, and soil carbon enhancement projects as part of their climate strategies9.

Table 1 illustrates how nature-based solutions (NbS) are defined by leading international organizations. It provides a side-by-side comparison that highlights both similarities and divergences in institutional definitions. This table clarifies the conceptual foundations of NbS by contrasting emphases on climate mitigation, adaptation, or integrated management.

Climate mitigation through NbS

Carbon sequestration in forests, wetlands, and soils: Forests remain the most significant terrestrial carbon sinks, sequestering approximately 2.6 gigatons of CO2 annually through photosynthesis and biomass accumulation10. Reforestation and afforestation projects are particularly effective in enhancing long-term carbon storage while providing co-benefits such as biodiversity conservation and watershed protection.

Wetlands, including peatlands, mangroves, and salt marshes, are disproportionately important despite their limited spatial coverage. They store 20-30% of global soil carbon and have sequestration rates that surpass most terrestrial ecosystems. However, wetland degradation releases vast amounts of stored carbon, making their conservation and restoration a high-priority NbS11.

Soils also play a crucial role in carbon sequestration. Practices such as regenerative agriculture, cover cropping, and reduced tillage enhance soil organic carbon stocks. These practices not only mitigate climate change but also improve soil fertility, water retention, and resilience to drought.

| Table 1: | Comparative definitions of NbS across major organizations | |||

| Organization | Definition | Citation(s) |

| IUCN | Actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore ecosystems to address societal challenges while providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits |

Seddon et al.7 |

| IPCC | Ecosystem-based approaches that contribute to mitigation and adaptation by enhancing carbon sinks and reducing vulnerability to climate impacts |

Sarabi et al.8 |

| UNFCCC | Integrated ecosystem management strategies embedded in NDCs to achieve Paris Agreement goals |

Ellis et al.9 |

| Columns: Organization, definition, citation, Abbreviations: IUCN: International Union for Conservation of Nature, IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and UNFCCC: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change | ||

| Table 2: | Carbon sequestration potential of different ecosystems | |||

| Ecosystem | Average carbon sequestration potential (tCO2e/ha/year) | Citation(s) |

| Tropical forests | 05-10 | Wolff et al.10 |

| Temperate forests | 2-05 | Wolff et al.10 |

| Peatlands | 10-20 | Dorst et al.11 |

| Mangroves | 06-8 | Dorst et al.11 |

| Agricultural soils (regenerative practices) | 01-3 | Wolff et al.10 |

| Columns: Ecosystem, average carbon sequestration potential (tCO e/ha/yr), Citation. Abbreviation: tCO e/ha/yr: Tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per hectare per year, values are reported as means or ranges taken from published literature | ||

Comparative effectiveness of NbS vs engineered solutions: The NbS are increasingly compared with engineered solutions such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies. While CCS can capture emissions at point sources, NbS provide multifunctional benefits: They sequester carbon, enhance biodiversity, regulate hydrological cycles, and support livelihoods. Studies show that NbS can deliver up to 37% of the cost-effective CO2 mitigation needed by 2030 to keep global warming below 2°C, making them a cornerstone of climate policy10.

Engineered solutions, though technologically advanced, often lack the co-benefits of NbS and can be costlier to implement at scale. For example, large-scale CCS projects require significant infrastructure and energy inputs, whereas NbS leverage natural processes that are self-sustaining once established11.

Table 2 illustrates the carbon sequestration potential of various ecosystems. It compares typical ranges of tonnes of CO2 equivalent stored per hectare per year across different land types. The table highlights which ecosystems (e.g., forests, peatlands, mangroves) provide the greatest climate mitigation benefits.

Co-benefits of NbS for climate and society: Beyond carbon sequestration, NbS delivers a wide range of co-benefits. They enhance biodiversity by restoring habitats, improve water quality through natural filtration, and reduce disaster risks by buffering against floods and storms12. Urban NbS, such as green roofs and urban forests, mitigate heat island effects, improve air quality, and enhance mental well-being for city dwellers13.

The NbS also contributes to socio-economic resilience. For example, mangrove restoration projects not only sequester carbon but also support fisheries, protect coastal communities from storm surges, and provide timber and non-timber products. Similarly, agroforestry systems improve food security while enhancing soil fertility and carbon storage14.

Challenges and limitations of NbS: Despite their promise, NbS face several challenges. One major limitation is scalability: While small-scale projects demonstrate success, scaling them up to national or global levels requires substantial financial investment and governance coordination15.

| Table 3: | Strengths and weaknesses of key decision-support frameworks | |||

| Framework | Strengths | Weaknesses | Citation(s) |

| MCDA (AHP, TOPSIS) | Integrates multiple objectives, stakeholder involvement |

Sensitive to the criteria weighting |

Thompson et al. 17 |

| GIS-based spatial optimization |

Captures spatial heterogeneity; scalable |

Data-intensive; computationally demanding |

Pasipamire and Muroyiwa18 |

| Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms |

Handles complex trade-offs; global optimum search |

High computational cost | Hafferty et al.19 |

| Columns: Framework, strengths, weaknesses, citation, Abbreviations: MCDA: Multi-criteria decision analysis, GIS: Geographic information system, strengths and weaknesses are summarized from cited studies in the manuscript | |||

Another challenge is the risk of greenwashing, where projects are labeled as NbS without delivering genuine ecological or social benefits. Ensuring robust monitoring, reporting, and verification frameworks is essential to maintain credibility.

Finally, NbS must be implemented with equity and justice in mind. Projects that displace local communities or fail to recognize indigenous land rights can exacerbate social inequalities. Inclusive governance and participatory approaches are therefore critical for the long-term success of NbS16.

ALGORITHMIC APPROACHES TO PRIORITIZATION UNDER UNCERTAINTY

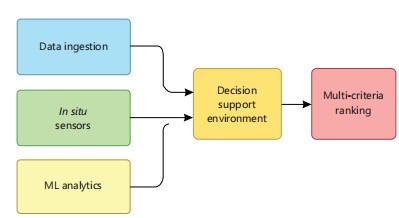

In the face of deep uncertainties inherent in climate projections, socio-economic dynamics, and ecosystem responses, algorithmic frameworks enable systematic prioritization of nature-based solutions (NbS). This section reviews recent advances in decision-support tools, machine learning, uncertainty quantification, and data integration, highlighting their capabilities and limitations for NbS planning under uncertainty.

Decision-support tools and models: Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) structures complex NbS planning problems by combining environmental, social, and economic criteria into a single evaluation framework. A recent critical review found that MCDA methods, such as AHP and direct ranking, help integrate diverse stakeholder preferences and ecosystem benefits, but their effectiveness depends on transparent criteria weighting and expert involvement17.

Spatial optimization and GIS-based prioritization tools extend MCDA by mapping suitability and identifying optimal intervention sites. Landscape and Urban Planning demonstrated a GIS-MCDA framework that accounts for land cover, hydrology, and urban heat island effects, enabling scalable site selection for green-blue infrastructure18. Evolutionary multi-objective algorithms further refine solutions by balancing trade-offs between carbon sequestration, flood control, and biodiversity gains, though they often require substantial computational resources and data inputs19.

Table 3 elucidates major decision-support frameworks for NbS as discussed above. It systematically presents their strengths (e.g., transparency, flexibility) alongside weaknesses (e.g., high data demands, complexity). This table enables practitioners to choose appropriate tools by comparing methodological trade-offs.

Machine learning and AI in NbS planning: Predictive modeling using machine learning (ML) is transforming NbS planning by forecasting ecosystem service provision under current and future conditions. A global synthesis showed that random forests, gradient boosting, and deep neural networks can predict habitat suitability, carbon storage, and flood mitigation capacity with 80-95% accuracy when trained on remote sensing and field data20. Such models allow planners to identify high-value restoration or conservation sites before implementation.

|

Under climate and socio-economic uncertainty, scenario analysis integrated with ML enhances resilience planning. A recent study applied ensemble neural networks combined with Monte Carlo scenario simulation to evaluate NbS performance across RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 pathways. This approach quantified distributional risks of flood reduction and urban cooling services, enabling decision-makers to compare trade-offs between low- and high-emission futures21.

Figure 1 is a schematic of an AI-driven NbS prioritization pipeline showing the flow from data ingestion→model training→scenario simulation→multi-criteria ranking. Emphasizes how algorithmic and decision-support components work together to prioritize NbS under uncertainty and support trade-off analysis.

Uncertainty quantification and risk assessment: Sources of uncertainty in NbS planning include variability in climate model outputs, divergent socio-economic trajectories, and non-linear ecological responses. An open-source climate risk platform study applied a PAWN sensitivity analysis to quantify the contributions of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability uncertainties to heat-stress risk. They found that choice of climate data source accounted for 40% of total uncertainty, underscoring the need for ensemble approaches22.

Robust decision-making frameworks address these uncertainties by optimizing NbS portfolios across a range of plausible futures. Dynamic adaptive policy pathways, which iteratively update strategies as new information emerges, provide a structured way to plan under deep uncertainty, balancing short-term actions and long-term flexibility23.

Sensitivity analysis further refines risk assessments by identifying critical parameters. In flood risk modeling for NbS interventions, local soil infiltration rate and vegetation growth assumptions were shown to drive 60% of outcome variability. Applying variance-based sensitivity indices helped prioritize data collection efforts to reduce uncertainty where it matters most24.

Table 4 illustrates the main sources of uncertainty in NbS planning. It pairs each uncertainty source (e.g., climate projections, socio-economic variability, ecological responses) with mitigation strategies. The table emphasizes the importance of risk management through ensembles, scenario planning, and adaptive monitoring.

|

| Table 4: | Primary sources of uncertainty in NbS planning and mitigation strategies | |||

| Source of uncertainty | Description | Mitigation strategies | Citation(s) |

| Climate model projections | Variation across GCMs and emission scenarios |

Ensemble modeling; bias correction |

Townsend et al.22 |

| Socio-economic pathways | Divergent development trajectories and policy choices |

Scenario planning; stakeholder co-creation |

Meraj and Hashimoto23 |

| Ecological response | Non-linear thresholds, feedbacks, and species interactions |

Adaptive management; targeted ecological monitoring |

Alipour et al.24 |

| Columns: Source of uncertainty, description, mitigation strategy, citation. Abbreviations: RCPs: Representative concentration pathways, SSPs: Shared socio-economic pathways, Strategies include ensemble modeling, scenario testing, and continuous monitoring | |||

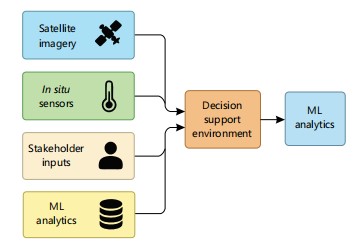

Integration of data and technology: Remote sensing and big data analytics are foundational for real-time NbS monitoring and validation. The Digital Twin Earth concept uses high-resolution satellite, LiDAR, and ground-based sensor streams to synchronize a virtual model with the physical landscape, enabling simulation of NbS impacts on hydrology and carbon fluxes25. Such digital twins support continuous performance tracking, early warning of system failures, and rapid scenario testing without field deployment.

Achieving seamless interoperability across diverse data sources and analytical platforms remains challenging. Standards for data exchange (e.g., OGC SensorThings API), common ontologies for NbS attributes, and cloud-based integration architectures are emerging to link GIS, ML models, and digital twin frameworks. A recent review in the ISPRS Journal highlighted architectures that leverage microservices, containerization, and open-source middleware to facilitate scalable, multi-tenant NbS monitoring systems26.

Figure 2 is a system architecture illustrating multi-source data integration: Satellite imagery, in-situ sensors, stakeholder inputs, and ML databases converging into a Decision Support Environment. Shows how heterogeneous data streams are integrated to inform operational analytics and feed back into ML workflows.

EQUITY, GOVERNANCE, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Nature-based solutions (NbS) are celebrated for their multifunctional benefits, yet their success hinges on fair and inclusive implementation, robust governance, and forward-looking research agendas. This section examines equity and justice in NbS, governance frameworks, implementation barriers, and future directions to ensure NbS delivers on both ecological and social promises.

|

| Table 5: | Dimensions of equity with examples in NbS projects | |||

| Equity dimension | Description | NbS example | Citation(s) |

| Distributional | Fair sharing of ecosystem service benefits and disamenities |

Urban green belts reducing heat Islands in Medellín, Colombia |

Basnou et al.27 |

| Procedural | Inclusive, transparent decision-making and stakeholder engagement |

Co-design of urban wetlandsin Melbourne, Australia | Wickham et al.28 |

| Recognitional | Respecting and integrating diverse knowledge, cultures, and worldviews |

Indigenous-led forest restoration in British Columbia, Canada |

Tozer et al.29 |

| Columns: Equity Dimension, Description, NbS Example, Citation. No abbreviations are used; all equity terms (distributional, procedural, recognitional) are written in full. Examples are illustrative cases demonstrating how each equity type manifests in practice | |||

Equity and justice in NbS implementation: Equity in NbS encompasses three interrelated dimensions:

| • | Distributional equity, which concerns the fair allocation of NbS benefits and burdens among social groups | |

| • | Procedural equity, which ensures inclusive decision-making processes | |

| • | Recognitional equity, which acknowledges diverse identities, values, and knowledge systems27 |

Studies show that without explicit equity goals, NbS risk reinforces existing injustices. For example, upland river restoration projects in Southeast Asia increased flood protection for urban neighborhoods but neglected downstream communities, shifting flood risk rather than alleviating it. Conversely, participatory mangrove restoration in the Sundarbans integrated women’s coastal livelihoods, recognizing their local ecological knowledge thus achieving both ecological resilience and social empowerment27. Effective NbS require embedding equity at all stages: From project design through monitoring and evaluation28.

Table 5 illustrates the dimensions of equity relevant to NbS projects. It defines distributional, procedural, and recognitional equity and provides project-based examples of each. This table shows how fairness and justice considerations are embedded in NbS practice.

GOVERNANCE AND POLICY FRAMEWORKS

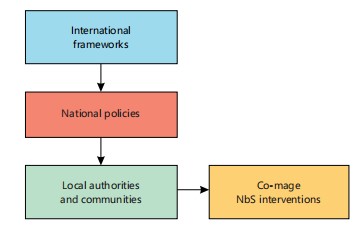

International and national strategies: Global agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Paris Agreement increasingly mandate NbS for climate mitigation and biodiversity targets30. At the national level, the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 and China’s Ecological Civilization policy integrate NbS into land-use planning, though implementation gaps persist. Effective governance hinges on aligning international commitments with Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and biodiversity strategies31.

|

| Table 6: | Key barriers to NbS implementation with potential solutions | |||

| Barrier | Description | Potential solution | Citation(s) |

| Financial gaps | Short-term funding cycles; high upfront costs |

Green bonds; blended public-private finance structures |

van der Jagt et al.32 |

| Institutional fragmentation | Multiple agencies with siloed mandates |

Inter-agency NbS task forces; cross-sectoral platforms |

Dempere et al.33 |

| Policy misalignment | Conflicting sectoral incentives | Policy audits; alignment of subsidies with NbS goals |

Karasaki et al.34 |

| Greenwashing | Lack of standardized NbS definitions and metrics |

Adoption of IUCN Global Standard for NbS; third-party audits |

Karasaki et al.34 |

| Columns: Barrier, description, potential solution, citation. Abbreviations: NGO: Non-governmental organization, MRV: Monitoring, reporting and verification, Solutions include financing mechanisms, governance reforms, and accountability tools | |||

Local governance, indigenous knowledge, and community participation: Strong local governance underpins successful NbS. Studies of community forest management in Nepal demonstrate that devolving decision-making power to local user groups enhances both ecological outcomes and social cohesion31. Incorporating indigenous governance systems, such as Canada’s Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) recognizes traditional custodianship and embeds Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) in NbS planning31.

Figure 3 is a flowchart of multi-level governance where international frameworks cascade into national policies and then empower local authorities and communities. A lateral arrow highlights the collaborative/co-management role of local actors in implementing NbS interventions.

CHALLENGES AND BARRIERS

Despite policy advances, NbS face multiple hurdles:

| • | Financial constraints: Limited access to long-term finance deters large-scale NbS; green bonds and blended finance mechanisms remain underutilized32 | |

| • | Institutional fragmentation: Overlapping mandates across forestry, water, and urban agencies create coordination challenges33 | |

| • | Policy misalignments: Sectoral policies (e.g., agricultural subsidies) can counteract NbS incentives, leading to perverse outcomes | |

| • | Greenwashing risks: Without rigorous standards, projects may be labeled as NbS without delivering genuine co-benefits34 |

Table 6 illustrates the barriers to NbS implementation and potential solutions. It lists financial, institutional, policy, and social challenges alongside recommended remedies. This table provides a concise problem solution guide for decision-makers and practitioners.

FUTURE RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Advancing algorithmic fairness in NbS prioritization.

As algorithmic tools guide NbS site selection and resource allocation, ensuring algorithmic fairness is critical. Incorporating fairness constraints in spatial optimization models can prevent systematic biases against marginalized areas35.

Integrating equity, resilience, and mitigation: Future NbS agendas must weave equity into resilience and mitigation goals. Research should explore co-optimization frameworks that balance carbon sequestration targets with social impact metrics.

Interdisciplinary collaboration and policy innovation: Addressing NbS complexity demands cross-disciplinary teams ecologists, social scientists, economists, and data scientists alongside policymakers. Co-produced knowledge and adaptive governance models will be essential to respond to evolving ecological and social challenges35.

Figure 4 is a roadmap infographic, showing four prioritized milestones for NbS research and practice: embedding equity in algorithms, refining governance, securing sustainable finance, and fostering transdisciplinary partnerships. A winding path with numbered, color-coded markers indicates sequencing and strategic emphasis for future work.

CONCLUSION

Nature-based solutions (NbS) hold significant potential for climate mitigation, resilience, biodiversity restoration, and local well-being when designed and governed thoughtfully. Realizing this potential requires rigorous monitoring and independent verification to translate modeled benefits into demonstrable outcomes. Interoperable data systems and transparent decision-support tools are essential for managing uncertainty and minimizing algorithmic bias. Equitable, participatory governance that respects indigenous stewardship and secures free, prior, and informed consent must be central to NbS implementation. Addressing social rights and local priorities ensures that ecological gains do not generate harmful trade-offs. Scaling NbS depends on sustainable finance, aligned sector incentives, and long-term commitments from public and private actors. Investment in interdisciplinary capacity building and practitioner networks will accelerate the translation of pilots into policy-relevant programs. Future research should focus on co-optimizing mitigation, adaptation, and social objectives through field trials and comparative studies. By embedding fairness, transparency, and adaptive evaluation into design, NbS can achieve accountable, evidence-based, and durable impacts that are both equitable and effective.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This manuscript highlights the potential of nature-based solutions (NbS) to deliver climate mitigation, biodiversity conservation, and human well-being. Ecosystems such as forests, wetlands, and soils provide carbon sequestration alongside co-benefits including water regulation, disaster risk reduction, and livelihood support. The study emphasizes inclusive governance, indigenous stewardship, and robust decision-support tools to ensure equitable and resilient implementation. Sustainable finance, technological innovations like remote sensing, and adaptive management are identified as key enablers for scaling NbS. The paper offers a roadmap for designing, implementing, and monitoring NbS that are both scientifically rigorous and socially just.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely acknowledge the support, guidance, and resources provided by our colleagues and affiliated institutions throughout the course of this work. We are also deeply grateful to the reviewers and editors whose insightful feedback strengthened the quality and clarity of this manuscript. Above all, we appreciate everyone whose contributions, both direct and indirect, made this study possible.

- Seddon, N., A. Smith, P. Smith, I. Key and A. Chausson et al., 2021. Getting the message right on nature‐based solutions to climate change. Global Change Biol., 27: 1518-1546.

- Frantzeskaki, N. and T. McPhearson, 2022. Mainstream nature-based solutions for urban climate resilience. BioScience, 72: 113-115.

- Yang, S., L. Ruangpan, A.S. Torres and Z. Vojinovic, 2023. Multi-objective optimisation framework for assessment of trade-offs between benefits and co-benefits of nature-based solutions. Water Resour. Manage., 37: 2325-2345.

- Goodwin, S., M. Olazabal, A.J. Castro and U. Pascual, 2025. A relational turn in climate change adaptation: Evidence from urban nature-based solutions. Ambio, 54: 520-535.

- Cook, E.M., Y. Kim, N.B. Grimm, T. McPhearson and P. Anderson et al., 2025. Nature-based solutions for urban sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 122.

- Wickenberg, B., K. McCormick and J.A. Olsson, 2021. Advancing the implementation of nature-based solutions in cities: A review of frameworks. Environ. Sci. Policy, 125: 44-53.

- Seddon, N., A. Chausson, P. Berry, C.A.J. Girardin, A. Smith and B. Turner, 2020. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, 375.

- Sarabi, S., Q. Han, A.G.L. Romme, B. de Vries, R. Valkenburg and E. den Ouden, 2020. Uptake and implementation of nature-based solutions: An analysis of barriers using interpretive structural modeling. J. Environ. Manage., 270.

- Ellis, P.W., A.M. Page, S. Wood, J. Fargione and Y.J. Masuda et al., 2024. The principles of natural climate solutions. Nat. Commun., 15.

- Wolff, E., H.A. Rauf and P. Hamel, 2023. Nature-based solutions in informal settlements: A systematic review of projects in Southeast Asian and Pacific countries. Environ. Sci. Policy, 145: 275-285.

- Dorst, H., A. van der Jagt, H. Toxopeus, L. Tozer, R. Raven and H. Runhaar, 2022. What’s behind the barriers? Uncovering structural conditions working against urban nature-based solutions. Landscape Urban Plann., 220.

- Vogel, B., L. Yumagulova, G. McBean and K.A.C. Norris, 2022. Indigenous-led nature-based solutions for the climate crisis: Insights from Canada. Sustainability, 14.

- Nyika, J. and M.O. Dinka, 2022. Integrated approaches to nature-based solutions in Africa: Insights from a bibliometric analysis. Nature-Based Solutions, 2.

- Reed, G., N.D. Brunet, D. McGregor, C. Scurr, T. Sadik, J. Lavigne and S. Longboat, 2022. Toward Indigenous visions of nature-based solutions: An exploration into Canadian federal climate policy. Clim. Policy, 22: 514-533.

- Favero, F. and J. Hinkel, 2024. Key innovations in financing nature-based solutions for coastal adaptation. Climate, 12.

- Hölscher, K., N. Frantzeskaki, M.J. Collier, S. Connop and E.D. Kooijman et al., 2023. Strategies for mainstreaming nature-based solutions in urban governance capacities in ten European cities. npj Urban Sustainability, 3.

- Thompson, A., K. Bunds, L. Larson, B. Cutts and J.A. Hipp, 2023. Paying for nature‐based solutions: A review of funding and financing mechanisms for ecosystem services and their impacts on social equity. Sustainable Dev., 31: 1991-2066.

- Pasipamire, N. and A. Muroyiwa, 2024. Navigating algorithm bias in AI: Ensuring fairness and trust in Africa. Front. Res. Metrics Anal., 9.

- Hafferty, C., E.S. Tomude, A. Wagner, C. McDermott and M. Hirons, 2025. Unpacking the politics of nature-based solutions governance: Making space for transformative change. Environ. Sci. Policy, 163.

- Townsend, J. and R. Roth, 2023. Indigenous and decolonial futures: Indigenous protected and conserved areas as potential pathways of reconciliation. Front. Hum. Dyn., 5.

- Croese, S., M. Oloko, D. Simon and S.C. Valencia, 2021. Bringing the global to the local: The challenges of multi-level governance for global policy implementation in Africa. Int. J. Urban Sustainable Dev., 13: 435-447.

- Townsend, J., F. Moola and M.K. Craig, 2020. Indigenous peoples are critical to the success of nature-based solutions to climate change. FACETS, 5: 551-556.

- Meraj, G. and S. Hashimoto, 2025. Bridging the adaptation finance gap: The role of nature-based solutions for climate resilience. Sustainability Sci., 20: 1093-1107.

- Alipour, A., K. Jafarzadegan and H. Moradkhani, 2022. Global sensitivity analysis in hydrodynamic modeling and flood inundation mapping. Environ. Modell. Software, 152.

- Hazeleger, W., J.P.M. Aerts, P. Bauer, M.F.P. Bierkens and G. Camps-Valls et al., 2024. Digital twins of the earth with and for humans. Commun. Earth Environ., 5.

- Zuniga-Teran, A.A., A.K. Gerlak, A.D. Elder and A. Tam, 2021. The unjust distribution of urban green infrastructure is just the tip of the iceberg: A systematic review of place-based studies. Environ. Sci. Policy, 126: 234-245.

- Basnou, C., J. Pino, C. Davies, G. Winkel and R. de Vreese, 2020. Co-design processes to address nature-based solutions and ecosystem services demands: The long and winding road towards inclusive urban planning. Front. Sustainable Cities, 2.

- Wickham, S.B., S. Augustine, A. Forney, D.L. Mathews, N. Shackelford, J. Walkus and A.J. Trant, 2022. Incorporating place-based values into ecological restoration. Ecol. Soc., 27.

- Tozer, L., H. Bulkeley and L. Xie, 2022. Transnational governance and the urban politics of nature-based solutions for climate change. Global Environ. Polit., 22: 81-103.

- Mansuy, N., D. Staley, S. Alook, B. Parlee and A. Thomson et al., 2023. Indigenous protected and conserved areas (IPCAs): Canada's new path forward for biological and cultural conservation and Indigenous well-being. FACETS, 8.

- Toxopeus, H. and F. Polzin, 2021. Reviewing financing barriers and strategies for urban nature-based solutions. J. Environ. Manage., 289.

- van der Jagt, A.P.N., A. Buijs, C. Dobbs, M. van Lierop and S. Pauleit et al., 2023. With the process comes the progress: A systematic review to support governance assessment of urban nature-based solutions. Urban For. Urban Greening, 87.

- Dempere, J., E. Alamash and P. Mattos, 2024. Unveiling the truth: Greenwashing in sustainable finance. Front. Sustainability, 5.

- Karasaki, S., R. Morello-Frosch and D. Callaway, 2024. Machine learning for environmental justice: Dissecting an algorithmic approach to predict drinking water quality in California. Sci. Total Environ., 951.

- Ariluoma, M., A. Kinnunen, J. Lampinen, R. Hautamäki and J. Ottelin, 2024. Optimizing the co-benefits of biodiversity and carbon sinks in urban residential yards Front. Sustainable Cities, 6.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Anih,

D.C., Oko,

O., Joseph,

N.T., Abubakar,

N., Clement,

U.C., Wokoma,

I.B., Okere,

M.C., Ikharehon,

N., Tekeme,

E.M., Okorocha,

U.C. (2026). Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Mitigation, Resilience, and Environmental Management: A Review of Algorithmic and Equity-Focused Prioritization under Uncertainty. Trends in Environmental Sciences, 2(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.01.12

ACS Style

Anih,

D.C.; Oko,

O.; Joseph,

N.T.; Abubakar,

N.; Clement,

U.C.; Wokoma,

I.B.; Okere,

M.C.; Ikharehon,

N.; Tekeme,

E.M.; Okorocha,

U.C. Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Mitigation, Resilience, and Environmental Management: A Review of Algorithmic and Equity-Focused Prioritization under Uncertainty. Trends Env. Sci 2026, 2, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.01.12

AMA Style

Anih

DC, Oko

O, Joseph

NT, Abubakar

N, Clement

UC, Wokoma

IB, Okere

MC, Ikharehon

N, Tekeme

EM, Okorocha

UC. Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Mitigation, Resilience, and Environmental Management: A Review of Algorithmic and Equity-Focused Prioritization under Uncertainty. Trends in Environmental Sciences. 2026; 2(1): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.01.12

Chicago/Turabian Style

Anih, David, Chinonso, Okechukwu Oko, Nwanze Tobechukwu Joseph, Nusa Abubakar, Uguru Chukwudi Clement, Izubundu Benedicta Wokoma, Michael Chibuzor Okere, Norrell Ikharehon, Ebikonboere Mary Tekeme, and Ugochukwu Cyrilgentle Okorocha.

2026. "Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Mitigation, Resilience, and Environmental Management: A Review of Algorithmic and Equity-Focused Prioritization under Uncertainty" Trends in Environmental Sciences 2, no. 1: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.01.12

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.