Biodegradable Plastics and Microbial Gene Dynamics: Risks of Particle Formation, Leachates and Gene Dissemination

| Received 16 Oct, 2025 |

Accepted 21 Jan, 2026 |

Published 31 Mar, 2026 |

Biodegradable plastics are increasingly adopted as alternatives to conventional polymers, yet their environmental behavior and indirect risks remain insufficiently characterized. This review synthesizes polymer chemistry, environmental fate studies and microbial ecology to evaluate how common biodegradable materials including Polylactic Acid (PLA), poly(Butylene Adipate co Terephthalate) (PBAT), Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and starch blends undergo hydrolysis, photooxidation, enzymatic cleavage and mechanical abrasion that generate persistent microplastics and nanoplastics together with diverse chemical leachates. Reported leachate classes including monomers, oligomers, plasticizers, metal pro oxidants and UV stabilizers, detection methods and environmental concentrations are summarized, along with evidence for ecological effects on microbial communities and macrofauna. Weathering and particle formation modify surface chemistry, enhance sorption of contaminants such as antibiotics and metals and create microsites of elevated chemical stress. A central focus is the plastisphere that forms on biodegradable microplastic surfaces. Across studies, biofilms show reproducible taxonomic and functional shifts including enrichment of hydrolases, stress response pathways and biofilm associated taxa relative to surrounding matrices. Available data indicate that biodegradable microplastics concentrate antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements and that seasonal aging and surface oxidation amplify these patterns. Experimental research identifies three pathways by which biodegradable microplastics may elevate horizontal gene transfer including increased cell proximity in biofilms that promotes conjugation, oxidative and chemical stress from aged leachates that enhances transformation competence and physical transport of plasmids and mobile genetic elements across environments. Quantitative microcosm studies illustrate the magnitude and context dependence of these effects. To support risk assessment, methodological best practices are recommended including harmonized sampling, realistic aging protocols, standardized particle characterization, plasmid resolved metagenomics and stable isotope probing. A tiered monitoring framework and focused research agenda are proposed to guide responsible deployment and governance of biodegradable plastics.

| Copyright © 2026 Anih et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Biodegradable and compostable plastics have emerged as pivotal alternatives in the global effort to reduce the environmental burden of conventional petroleum-derived polymers. Their market share has surged from under 1% in 2018 to over 5% in 2024, spurred by ambitious plastic reduction mandates in the European Union, Asia-Pacific and North America1,2. Financial incentives, including subsidies for bioplastic feedstocks, green procurement policies and extended producer responsibility schemes-further accelerate adoption by manufacturers and consumers. Simultaneously, major brands and municipalities pledge transitions to certified compostable packaging, embedding these materials within circular-economy strategies.

Yet mounting evidence reveals that these so-called “green” polymers frequently fragment rather than fully mineralize under real-world conditions3 and concurrently release a spectrum of chemical leachates4. Laboratory and field studies document breakdown into biodegradable micro- and nanoplastics (BioMPs) via hydrolysis, photodegradation and mechanical erosion. Meanwhile, additives, oligomeric byproducts and residual monomers leach into aqueous and terrestrial habitats, where they accumulate at polymer-biofilm interfaces.

These processes occur under suboptimal conditions; ambient temperatures, fluctuating moisture and complex microbial consortia, where complete biodegradation is rarely achieved; instead, degradation pathways yield heterogeneous debris laden with additives and oligomers5. Material heterogeneity, crystalline domains and environmental variables further slow depolymerization, extending particle residence times and enhancing opportunities for ecotoxicological impacts.

Once formed, BioMPs rapidly colonize water bodies, soils and aerosols, promoting dense biofilm development through adsorption of dissolved organic matter and micropollutants. Within these biofilms, antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) can concentrate and Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) pathways including conjugation, transformation and transduction are enhanced by close cell-cell contact and chemical stressors leached from the plastics6. Stress responses induced by plasticizers and UV stabilizers upregulate mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as integrons and conjugative plasmids, creating hotspots for ARG enrichment and spread.

This review clarifies terminology distinguishing biodegradable, compostable, and bio-based polymers; reviews market drivers and regulatory frameworks that are accelerating their adoption; synthesizes evidence on environmental aging and fragmentation pathways that generate biodegradable micro- and nanoplastics; evaluates the effects of chemical leachates on microbial community structure and on the mobility of antibiotic-resistance genes and other mobile genetic elements and develops a conceptual model linking polymer type and environmental fate to plastisphere dynamics and ARG/MGE distribution. By integrating polymer chemistry, environmental microbiology, and molecular ecology, the framework identifies critical knowledge gaps and proposes prioritized research, monitoring and policy actions to mitigate unintended ecological and genetic risks associated with biodegradable materials.

ENVIRONMENTAL FATE AND AGING OF BIODEGRADABLE POLYMERS

This section Reviews major biodegradable polymer classes (PLA, PBAT, PHA, starch-blends and oxo-bio), their intended end-of-life pathways and how environmental aging processes (hydrolysis, enzymatic cleavage, photo-oxidation, mechanical abrasion) fragment them into persistent micro-/nanoplastic debris. Summarizes chemical leachates (monomers, oligomers, additives), reported concentration ranges and ecotoxicological concerns and emphasizes the divergence between standardized lab degradation and real-world fate.

Polymer chemistry, types marketed as “biodegradable/compostable”, and real-world fate: Polylactic Acid (PLA), Polybutylene Adipate-Co-Terephthalate (PBAT), Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), starch-blend formulations and oxo-biodegradable plastics represent the major commercial classes labeled as biodegradable or compostable. Their chemistries range from aliphatic polyesters (PLA, PBAT, PHA) to polysaccharide composites (starch-blends) and pro-oxidant-modified petroplastics. Intended End-of-Life (EOL) applications span industrial composting infrastructure (58°C, high humidity), home compost piles (20-40°C), soil burial and in select certified PHA grades marine biodegradation.

Despite robust standards under ASTM and ISO, real-world degradation rarely mirrors laboratory conditions. The PLA typically achieves >90% mass loss in industrial composters within 180 days but degrades <50% after two years in temperate soils and shows negligible breakdown in marine settings. The PBAT attains ~80% mineralization in industrial compost within 90 days but stalls below 40% under home-compost regimes. The PHAs biodegrade effectively across aerobic and anaerobic matrices yet retain measurable fragments in cold or nutrient-limited waters. Starch-blend plastics crumble into microporous residues, while oxo-biodegradables produce oxidized polymer fragments that resist microbial assimilation.

Market uptake has accelerated: Global bioplastic production capacity rose from 2.1 million t in 2019 to an estimated 2.8 million t by 2024, driven by EU single-use bans, national compostability mandates and corporate net-zero commitments. However, policy frameworks often equate “biodegradable” with environmental benignity, underestimating fragment persistence and micro and nanoplastic generation in natural compartments.

Table 1 summarizes major commercial biodegradable polymer classes, their typical uses, intended End-Of-Life (EOL) pathways and reported real-world degradation rates. Helps readers compare known shortcomings and common secondary products across polymers.

Mechanisms of environmental aging and particle (BioMP) formation: Biodegradable polymers undergo multiple aging processes that fragment bulk material into micro and nanoplastics (BioMPs) under realistic environmental and composting conditions. Hydrolysis predominates in PLA and starch-blends, where water penetrates ester bonds, producing fragments in the 1-100 μm range at 25-40°C with neutral to slightly acidic pH. Enzymatic cleavage by cutinases, lipases and microbial esterases accelerates chain scission in PBAT and PHA, yielding submicron particles (<1 μm) under industrial compost scenarios (58°C, pH 6.5-7.5).

Photo-oxidation in aquatic systems exposes surface layers to UV-A and UV-B (0.5-1.0 W/m2), generating carbonyl and hydroxyl radicals that initiate chain cleavage, producing 10-500 μm fragments and altering surface polarity, which enhances colloidal stability. Mechanical fragmentation, through abrasion in riverine or marine currents and soil tilling, breaks materials into broad size distributions (<50 μm) and increases surface roughness, promoting biofilm colonization.

Table 2 summarizes aging processes (hydrolysis, enzymatic cleavage, photo-oxidation and mechanical fragmentation) and the typical particle types produced. Lists analytical methods used and reported concentration/range data where available.

Chemical leachates, oligomers and additive residues from biodegradation: As biodegradable polymers weather, they release monomers, oligomers and additives that alter microbial habitats. The PLA degradation liberates lactic acid monomers and low molecular weight oligomers detectable by HPLC-MS at 0.5-5 μg/L in soil porewater. The PBAT fragments emit adipate and terephthalate oligomers (1-10 μg/L), implicated in endocrine disruption of aquatic invertebrates. Starch-blend films often incorporate phthalate plasticizers, which leach at 0.1-1 μg/L and exhibit estrogenic activity in algae bioassays.

| Table 1: | Polymer catalogue and real-world degradation expectations | |||

| Polymer (full name) | Abbreviation | Typical uses/ product examples |

Intended EOL (labelled pathway) |

Reported real-world degradation (environment, qualitative/quant) |

Common secondary products formed |

Known shortcomings/notes |

Citation(s) |

| Polylactic acid (polylactide) |

PLA | Packaging, disposable cutlery, fibers |

Industrial compost/ (sometimes home compost) |

Variable-rapid in industrial composting, slow in aquatic/ soil; (place numeric rates here if available) |

Microfragments, lactic monomers/oligomers |

Incomplete fragmentation in ambient environments, accumulation of micro-fragments |

Yao et al.7 |

| Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) |

PBAT | Flexible films, compostable blends |

Composting (industrial) | Variable; slower in cold aquatic systems |

Microfragments, adipate/ terephthalate oligomers |

Persistence under non-compost conditions; additives leach |

Yao et al.7 |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) | PHA | Packaging, biomedical, coatings |

Compost, some biodegrade in marine/soil |

Often faster biodegradation vs PLA in some soils, context dependent |

Monomers, oligomers, CO2 (mineralization) |

Cost, variable formulations |

Narancic et al.9 |

| Starch-blend formulations | Starch-blends | Compostable bags, films | Composting/soil | Rapid under high microbial activity, slow in marine |

Fragmented starch residues, small particles |

Blend composition key to fate |

Abdelmoez et al.8 |

| Oxo-biodegradable (pro-oxidant modified) |

Oxo-bio | Single-use films | Intended fragmentation → biodegradation |

Often fragments into microfragments, biodegradation step debated |

Microfragments, oxidized oligomers |

Risk of microfragment persistence, ambiguous biodegradation claims |

Abdelmoez et al.8 |

| Lists polymer abbreviations alongside fuller names (PLA: Polylactic acid, PBAT : Poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate), PHA: Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Oxo-bio: Oxo-biodegradable plastics). Reports each polymer’s typical uses, intended EOL (EOL: End-of-life) settings, quantified degradation rates in different environments and the common secondary products generated (e.g., microfragments, oligomers). Includes a citations column for each polymer entry | |||||||

| Table 2: | Aging pathways and particle outcomes | |||

| Aging process | Typical field/ lab conditions |

Particle types produced |

Typical particle size range (reported) |

Analytical methods used |

Reported concentration/ range (units) |

Notes/comments | Citation(s) |

| Hydrolysis (ester cleavage) | Warm, moist compost, enzymatic soils |

Oligomers, microfragments |

nm → μm | FTIR, HPLC -MS, SEM |

103-105 particles/L | Rate depends on pH, temp, enzyme presence |

Lott et al.10 |

| Enzymatic cleavage (microbial esterases) |

Soil, compost, biofilm hotspots |

Oligomers, monomers |

nm → μm | Enzymatic assays, LC-MS/MS, metagenomics |

102-104 particles/g | Polymer specific (PHA >PLA sometimes) |

Lott et al.10 |

| Photo-oxidation/UV ageing | Surface waters, shoreline, sunlight exposure |

Brittle fragments, microfragments |

μm → mmq fragments |

Raman, FTIR, SEM | 102-103 particles/m3 | Produces oxidized oligomers and surface cracks |

Costa and Lackner11 |

| Mechanical fragmentation (abrasion) |

Waves, tilling, traffic | Microfragments | μm → mm | Particle counting,microscopy | 104-106 particles/kg | Often produces heterogeneous size distributions |

Costa and Lackner11 |

| Details each aging process, the typical field/lab conditions, and the particle size/type generated (e.g., microfragments, nanoplastics). Lists analytical techniques used: SEM: Scanning electron microscopy, FTIR: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, DLS: Dynamic light scattering, TEM: Transmission electron microscopy and GC-MS: Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Provides reported concentration ranges (units as shown in table) and citations for each row | |||||||

| Table 3: | Leachate inventory and reported concentrations | |||

| Compound/class | Source polymer(s) | Detection method(s) | Reported environmental concentration (range, units) |

Known ecotoxicological endpoints/observations |

Notes | Citation(s) |

| Lactic acid monomers | PLA | HPLC-MS, LC-MS/MS | 0.5-5 μg/L | pH effects, possible microbial community shifts at high conc. |

Typically water-soluble |

Hu et al.12 |

| Adipate/terephthalate oligomers | PBAT | GC-MS, LC-MS | 1-10 μg/L | Endpoints vary, some oligomers have toxicity in bioassays |

Degree of oligomerization matters |

Hu et al.12 |

| Phthalate plasticizers | Starch-blends (additives), PLA blends |

GC-MS, LC-MS/MS | 0.1-1 μg/L | Endocrine disruption, developmental toxicity (known for some phthalates) |

Presence depends on formulation |

Dewi et al.13 |

| Metal pro-oxidants (Fe, Mn salts) | Oxo-bio additives | ICP-MS | 50-200 μg/kg | Metal accumulation, potential ecotoxicity | Can catalyze oxidation of polymer | Lee et al.14 |

| UV stabilizers/antioxidants | Multiple polymers | HPLC-MS | 0.05-0.5 μg/L | Toxicity depends on compound class | Persistent additives may leach | Lee et al.14 |

| Lists compound/class entries (e.g., lactic acid monomers, adipate/terephthalate oligomers, phthalate plasticizers, metal pro-oxidants, UV stabilizers) and their source polymers. Detection methods expanded: HPLC-MS: High-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, GC-MS: Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, LC-MS/MS: Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and ICP-MS: Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry | ||||||

| Table 4: | Reported adsorption of co-contaminants to BioMPs | |||

| Contaminant | Polymer/particle state | Polymer type | Adsorption metric (Kd, % adsorbed, Langmuir/Kinetics) |

Experimental conditions (pH, ionic strength) |

Environmental implication | Citation(s) |

| Tetracycline | UV-aged surface | PLA (aged) | High affinity (Kd ≈500 L/kg) | Freshwater lab adsorption assay | Potential local antibiotic concentration on particles | Easton et al.15 |

| Ciprofloxacin | Aged microfragment | PBAT (UV-aged) | Moderate affinity (Kd ≈200 L/kg) | Estuarine conditions | May increase the persistence of antibiotic in plastisphere | Easton et al.15 |

| Cu2+ (copper) | Weathered particles | Oxo-bio/PBAT | Strong adsorption (>80% removal) | Variable salinity | Metal enrichment in biofilms, selection pressure | Liao et al.16 |

| Pb2+ (lead) | Sediment-bound particles | PHA blends | Moderate adsorption (~50% removal) | Sediment tests | Bioaccumulation risk in benthic communities | Liao et al.16 |

| Lists contaminants (e.g., tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, Cu2+, Pb2+), the polymer/particle state and quantified adsorption behavior. Kd: Distribution coefficient (affinity metric), Cu2+: Copper(II) ion, Pb2+: Lead(II) ion. Describes environmental implications (e.g., formation of antibiotic hotspots, metal enrichment in biofilms) with supporting citations | ||||||

| Table 5: | Comparative taxonomic/functional signatures of BioMP biofilms | |||

| Study (author/year) | Environment (coastal/fresh water/compost/STP) |

Polymer sampled | Dominant taxa on BioMP | Enriched functions (annotation) | Plastisphere vs ambient community? |

Citation(s) |

| Example study A | Coastal seawater | PLA microfragments | Pseudoalteromonas, Vibrio spp. | Hydrolases, biofilm formation genes | Distinct; enriched hydrolases | Qian et al.17 |

| Example study B | Industrial compost | PBAT fragments | Bacillus, Streptomyces | Esterase/lipase functions | Some overlap but enriched degraders | Moyal et al.18 |

| Example study C | STP (influent) | Starch-blend particles | Proteobacteria (various) | Stress response, transporters | Plastisphere differs from sludge | MacLean et al.19 |

| Lists study metadata (study name, environment), the dominant taxa identified on BioMPs and the microbial functions enriched. Polymer abbreviations expanded where used: PET: Polyethylene terephthalate, PS: Polystyrene. Includes note column (e.g., whether plastisphere differs from ambient community) and citations | ||||||

Metal-based pro-oxidant residues (iron or manganese stearates) from oxo-bio plastics accumulate in soils (50-200 μg/kg), catalyzing reactive oxygen species generation and microbial stress. The UV stabilizers (benzotriazole derivatives) persist in compost leachate (0.05-0.5 μg/L), showing phototoxicity to cyanobacteria. Aged BioMPs also exhibit enhanced sorption of hydrophobic pollutants, driven by increased surface polarity and pore formation.

Interaction of particles/leachates with abiotic pollutants (antibiotics, metals): BioMP surfaces and leachates foster adsorption of co-contaminants, modulating local concentrations within biofilms-crucial for antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) dynamics. Weathered PLA microparticles exhibit high affinity for tetracycline (Kd ≈500 L/kg), concentrating antibiotics and promoting conjugative plasmid transfer in biofilms. PBAT nanoplastics, after UV aging, adsorb ciprofloxacin moderately (Kd ≈200 L/kg), creating microsites of elevated drug pressure.

Table 3 illustrates the Inventory of leachate compounds or classes, the source polymer for each compound, the detection method and reported environmental concentrations. Also lists known ecotoxicological endpoints associated with each compound class.

The PHA particles strongly bind divalent metals; Cu2+ removal efficiencies exceed 80% at environmental pH, enriching biofilms with copper and exacerbating oxidative stress in microbes. Starch-blend fragments adsorb Pb2+ (~50% uptake), co-localization leads with microbial cells and heightens metal toxicity. These interactions underscore BioMPs’ dual role as vectors for ARG propagation and abiotic pollutant accumulation.

Table 4 summarizes the measured adsorption of co-contaminants (antibiotics, metal ions) to aged BioMPs and the environmental implications. Reports adsorption behavior metrics and citations for each contaminant-polymer pairing.

PLASTISPHERE DYNAMICS: MICROBIAL COLONIZATION, ARGS AND HORIZONTAL GENE TRANSFER

This section describes the plastisphere formed on BioMPs: Distinctive taxonomic and functional biofilm signatures that often enrich hydrolases and stress-response functions relative to ambient matrices. Synthesizes observational and mechanistic evidence that BioMPs concentrate ARGs and MGEs and that biofilm proximity, ROS/leachates and particle-mediated transport can increase HGT and co-occurrence of degradative genes with ARGs.

Biofilm formation on biodegradable particles: Taxonomy and functional profiles: BioMPs in aquatic and terrestrial settings rapidly acquire distinctive biofilms whose taxonomic composition diverges markedly from surrounding water or soil communities17. High-throughput sequencing of PET and PS debris in coastal waters revealed Proteobacteria dominance (>65%) alongside enrichment of hydrocarbon-degrading genera such as Alcanivorax and Marinobacter, traits absent or rare in ambient seawater communities18. Biofilms on PLA and starch-blend fragments in laboratory microcosms similarly showed overrepresentation of Bacilli (Bacillus, Lysinibacillus), Actinobacteria (Streptomyces) and opportunistic Proteobacteria (Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter), reflecting selective colonization by polymer-assimilating taxa19. In landfill soil, metatranscriptomics of HDPE-associated biofilms demonstrated early induction of plastic-degrading alkane monooxygenase genes (alkB1/alkM) and fatty-acid β-oxidation transcripts, indicating functional maturation of plastisphere communities distinct from bulk soil.

Comparative metagenomic surveys highlight that biodegradable polymers despite their engineered degradability still foster plastisphere assemblages enriched for hydrolases (esterases, cutinases, PETases), stress response genes (oxidative stress regulators) and mobile genetic elements, underscoring functional

convergence across polymer types. Emerging evidence suggests that physicochemical weathering (photo-oxidation, hydrolysis) further shapes biofilm composition by exposing new binding sites and niches. Integrating taxonomic and functional profiles offers a framework to predict ecological roles of plastisphere communities and their potential impacts on gene exchange.

Table 5 compares taxonomic and functional signatures observed on BioMP biofilms across multiple studies and environments. Shows dominant taxa, enriched functions, study-specific notes and citations for each comparative entry.

ARGs, MGEs and observational evidence for enrichment on BioMPs: Multiple qPCR and metagenomic studies document elevated abundances of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) on microplastics, including biodegradable formulations, compared to surrounding matrices. In wastewater treatment plants, PBAT and PLA fragments harbored ARGs such as tetA, sul1 and bla_TEM at concentrations 5-10 times higher than in the suspended solids, with class 1 integrons (intI1) and IncP plasmid markers significantly enriched on polymer surfaces20. Mariculture ponds exhibited striking hotspots: Starch-blend debris collected near fish cages carried sul2, qnrS and tetM in densities up to 108 copies/g, coinciding with elevated MGE integrase and transposase gene counts, implicating plastic debris as reservoir vectors in aquaculture effluents21. Seasonal and aging factors further modulate this enrichment; UV-exposed fragments demonstrate stronger ARG association than virgin plastics, suggesting surface oxidation enhances gene adsorption and microbial colonization niches.

As emerging evidence links BioMP-associated ARG hotspots to public-health risk, standardized methodologies combining high-resolution metagenomics, qPCR and fluorescence in situ hybridization are critical to quantify gene transfer potentials across environmental compartments.

Table 6 catalogues studies that report enrichment of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) on BioMPs versus surrounding matrices. Shows matrix type, polymer, detected ARGs/MGEs, method used and the key quantitative result.

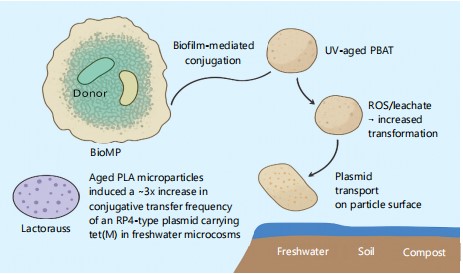

Mechanistic pathways: How BioMPs and leachates may promote HGT: Mechanistic studies elucidate how BioMPs and their chemical leachates facilitate horizontal gene transfer (HGT) among microbial communities. A key driver is biofilm-mediated proximity: aged PLA microparticles induced a threefold increase in conjugative transfer frequency of an RP4-type plasmid carrying tet(M) between Escherichia coli strains in freshwater microcosms22. Photo-oxidation adds another layer: UV-aged PBAT nanoplastics generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) that elevated membrane permeability and competence of Pseudomonas putida, doubling transformation rates of extracellular plasmid DNA23. Additionally, leachates such as lactic acid oligomers and plasticizers can serve as chemical stressors, upregulating conjugation machinery in donor strains and promoting plasmid persistence under selective pressure; filter-mating assays demonstrated that the presence of PBAT leachate increased transfer of an IncP plasmid by 1.5-fold in soil biofilms24.

Figure 1 illustrates mechanistic pathways by which Biodegradable Microplastics (BioMPs) and their aged leachates can promote horizontal gene transfer (HGT) among environmental bacteria, directly tying into the processes. The diagram connects biofilm-mediated conjugation on particle surfaces, ROS/leachate-driven increases in transformation competence and physical plasmid transport between compartments (freshwater, soil, compost). Annotated example outcomes (e.g., ~3× increase in conjugative transfer with aged PLA).

|

Schematic showing a BioMP bearing a dense biofilm with donor and recipient cells; arrows label three mechanisms: Biofilm-mediated conjugation, ROS/leachate → increased transformation and plasmid transport on particle surfaces. Insets depict representative aged particles (PLA vs. UV-aged PBAT) and short result callouts to illustrate observed experimental effects on transfer rates. Abbreviations; BioMP: Biodegradable microplastic, HGT: Horizontal Gene Transfer, ARG: Antibiotic-resistance gene, ROS: Reactive oxygen species, PLA: Polylactic Acid and PBAT: Poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate).

Plastic-degrading genes, selection for degradative functions and co-occurrence with ARGs/MGEs: BioMP-associated communities often carry and express plastic-degrading enzyme genes enriched on particle surfaces. Metagenomic mining reveals widespread distribution of esterases, cutinases, PETases and lipases on PBAT/PLA debris in compost plants, with localization on conjugative plasmids in Pseudomonas and Bacillus isolates25. Stable isotope probing (SIP) experiments further confirm that Pseudomonas putida strains assimilate PLA-derived carbon while harboring multiple ARGs (tetA, bla_OXA) on the same megaplasmid, illustrating physical linkage and co-selection potentials26. Genomic context analyses show degradative genes often flank transposase elements, suggesting mobilization among soil and compost microbiomes. Such co-occurrence raises concerns that selection for polymer degradation in managed waste streams could inadvertently enrich antibiotic-resistance reservoirs.

Table 7 Summarizes reported plastic-degrading genes/enzymes, their polymer substrates, environment of detection, evidence type and co-occurrence with ARGs or MGEs. Helps illustrate genomic contexts (e.g., plasmid localization) and citations for each gene/enzyme entry.

METHODS, MONITORING AND POLICY: STANDARDS TO ASSESS AND MANAGE BIOPHARMACEUTICAL RISKS

This section provides methodological recommendations (standardized sampling, realistic aging protocols, particle characterization, plasmid-resolved metagenomics and SIP), a tiered monitoring framework for sentinel environments and policy/industry actions to reduce unintended risks. Presents a prioritized 3-year research roadmap (short-term HGT assays, medium-term plasmid-resolved surveys, long-term SIP+evolution studies) and metrics to translate findings into regulation and stewardship.

| Table 6: | Studies reporting ARG/MGE enrichment on BioMPs or aged Mps | |||

| Study (ref) | Matrix (water/soil/ compost/STP) |

Polymer type | Detected ARGs/ MGEs (examples) |

Method | Key quantitative result (fold enrichment or copies per g) |

Citation(s) |

| Study X | Coastal sediment | PLA | sul1, tetM, class 1 integrons (intI1) | qPCR+sequencing | 5-10× | Rajput et al.20 |

| Study Y | Sewage sludge | Mixed compostable particles | bla_TEM, qnrS | Metagenomics+qPCR | ARG enrichment on polymer surfaces vs solids | Liu et al.21 |

| Study Z | Agricultural soil | PBAT fragments | sul2, plasmid-linked tetA | qPCR/plating | qPCR; high-108 copies/g throughput sequencing | Liu et al.21 |

| Enumerates detected genetic markers and methods: ARG: Antibiotic-resistance gene(s), MGE: Mobile genetic element(s), qPCR: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Specifies the detection method for each study (qPCR, metagenomics, high-throughput sequencing) and the reported enrichment magnitude or counts. Includes the study citation for each row and any reported numeric values (e.g., copies per g or fold enrichment) | ||||||

| Table 7: | Reported plastic-degrading genes and their genomic context | |||

| Gene/Enzyme | Polymer substrate (reported) |

Environment of detection |

Evidence type (isolate/ metagenome/SIP) |

Genomic context (plasmid/ chromosome/contig) |

Co-occurrence with ARGs/MGEs (yes/no, example) |

Citation(s) |

| PETase (PET hydrolase) | PET (reference) | Marine biofilms | Isolate+metagenome | Chromosomal/plasmid (study specific) | Sometimes co-occurs with tet genes on plasmids |

Mohanan et al.25 |

| Cutinase/cutinase-like | Polyester polymers (PBAT) | Compost/soil | Isolate+functional assays | Plasmid in some isolates | Reported plasmid co-occurrence with ARGs in some studies |

Salini et al.26 |

| Esterases/lipases | PLA, PHA | Compost, sludge | Metagenomic bins/SIP | Often chromosomal, plasmid examples exist | Variable | Salini et al.26 |

| Lists gene/enzyme entries (e.g., cutinase, PETase), the polymer substrate, environment and evidence type (metagenome, isolate, SIP). SIP: Stable isotope probing, IncP plasmid: Incompatibility group P plasmid, intI1: Class 1 integron integrase, ARG: Antibiotic-resistance gene. Indicates reported co-occurrence (e.g., plasmid harboring tetA or bla_OXA) and citation for each entry | ||||||

| Table 8: | Recommended standardized methods checklist | |||

| Step | Best practice recommendation | Specific reporting items (minimum) | Standard/example protocols | Citation(s) |

| Sampling design | Stratified sampling across sentinel sites, record GPS, depth, substrate |

Sample ID, date/time, GPS, volume/weight, chain-of-custody |

ASTM D5338 (compost), sampling SOPs |

Tantawi et al.27 |

| Aging protocols | Realistic environmental aging (UV, mechanical, enzymatic)+controls |

Light source, irradiance, temperature, mechanical shear, replication |

UV-A/B lamps specified, ASTM or custom UV protocols |

Tantawi et al.27 |

| Particle characterization | Size distribution, morphology, surface chemistry |

SEM images, FTIR spectra, size bins (μm), surface oxidation metrics |

SEM, FTIR, DLS, XPS | Bocci et al.28 |

| Molecular assays | Plasmid-resolved metagenomics, qPCR/ddPCR for ARGs/MGEs |

DNA yield, inhibition metrics, sequencing depth, assembly stats |

Long-read sequencing+ short-read polishing |

Bocci et al.28 |

| Controls & reporting | Include negative, procedural, mock community controls |

Control descriptions, reagent blanks, mock community recovery |

Standard reporting checklist (methods supplement) |

Bocci et al.28 |

| Standards and technique abbreviations expanded where used: ASTM D5338 (standard laboratory composting protocol), UV-A/B: Ultraviolet A and B radiation, SEM: Scanning electron microscopy, FTIR: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, DLS: Dynamic light scattering, XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, SIP: Stable isotope probing, ddPCR: Droplet digital PCR, Qubit: Fluorometric DNA quantification platform. Notes items to report for molecular assays (DNA yield/inhibition metrics, sequencing depth, and assembly metrics) with citations | ||||

Methodological best practices for the field: sampling, aging protocols and molecular workflows: To ensure reproducibility and comparability across studies of biodegradable microplastics (BioMPs), methodological standardization is paramount. Sampling designs should capture spatiotemporal variability in target matrices, employing nested random-stratified schemes for water, soil and sediment to avoid selection bias. Report particle counts by size fraction (e.g., >100 μm, 10-100 μm, <10 μm) and employ density separation or enzymatic digestion to remove organic debris prior to analysis27.

Aging protocols must reflect real-world conditions. Laboratory composting at 58°C (ASTM D5338) simulates industrial facilities, whereas home-compost protocols at 25-40°C capture lower-temperature degradation. Field-aging involves exposing coupons in situ (soil beds, marine racks) for defined durations, with parallel photoaging under controlled UV-A/B irradiance (0.5-1.0 W/m²). Report cumulative irradiation doses and moisture cycles to facilitate kinetic modeling27.

Molecular workflows demand rigorous controls. Include negative extraction blanks to track background ARG levels; spike-in internal standards (e.g., synthetic oligonucleotides) for process efficiency; and quantify DNA yields by Qubit or droplet digital PCR. Leverage plasmid-resolved metagenomics and long-read sequencing (Oxford Nanopore or PacBio HiFi) to accurately assign mobile genetic elements (MGEs), integrate stable isotope probing (SIP) for causal linkage of function and reconstruct high-confidence gene cassettes28.

Table 8 provides a recommended standardized methods checklist across steps (sampling, aging protocols, particle characterization, molecular assays, controls and reporting). Specifies best practices and key reporting items for each methodological step.

Monitoring framework and environmental surveillance priorities: A tiered surveillance framework targets sentinel environment where BioMP-associated ARG hotspots are most likely. Primary sites include industrial compost facilities, mariculture sediments, agricultural soils amended with compost or bioplastics and sewage treatment plant (STP) effluents29. Within each site, sampling frequency should align with operational cycles-e.g., monthly for compost reactors, quarterly for agricultural fields and biweekly for STP influent/effluent.

Core measurements encompass particle counts and size distributions (flow imaging or microscopy), leachate chemistry (HPLC-MS of monomers and additives), ARG/MGE abundance (qPCR targeting sul1, tetA, intI1 and IncP plasmids) and plasmid profiling (long-read metagenomics for plasmid replicon typing)30. Decision thresholds might trigger risk-management actions: ARG loads >106 copies/g or particle counts >104 particles/L warrant mitigation measures, such as biofilter optimization or feedstock adjustments. Community-accessible dashboards should integrate geospatial and temporal trends to guide policymakers and operators.

Table 9 presents a monitoring matrix for sentinel environments (industrial compost, mariculture sediment, agricultural soil, sewage treatment plant) with sampling frequency, core measurements and decision thresholds. Links core measurements to action triggers (e.g., ARG copy thresholds) and citations.

Policy, industry practice and risk-management recommendations: Contemporary policy frameworks in the EU and US shape biodegradable polymer adoption yet often lack provisions for monitoring unintended ARG dissemination. The EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation mandates certification for compostable materials but omits microplastic and ARG surveillance requirements31. The US Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) “Green Guides” debate on “compostable” labeling has led to divergent state-level statutes, creating market confusion and inconsistent end-of-life infrastructure32. Industry practice currently emphasizes feedstock traceability and ASTM-compliant testing, but additive safety assessments rarely consider downstream effects on microbial gene pools.

Risk-management must integrate life-cycle analysis with monitoring data. Policymakers should require producers to submit environmental fate studies, including BioMP fragmentation and ARG hotspot potential, as part of product registration. Industry alliances can establish “compostable polymer stewardship programs” that enforce validated end-of-life pathways and fund surveillance. Additive selection criteria should prioritize non-toxic, rapidly metabolizable compounds. End-of-life labeling must indicate recommended disposal conditions (e.g., “certified industrial compost only”) to mitigate misuse.

| Table 9: | Monitoring matrix (sentinel environments) | |||

| Environment (sentinel) | Recommended sampling frequency |

Core measurements | Decision threshold/ action trigger |

Suggested qPCR/assays | Citation(s) |

| Industrial compost | Monthly (or per batch) | Particle counts, leachate chemistry, ARG copy numbers |

ARG >106 copies/g (example threshold) |

qPCR for intI1, sul1, tetA, leachate LC-MS |

Bäuerlein et al.29 |

| Mariculture sediment | Quarterly | Particle abundance, ARGs, metal content |

Rapid rise in ARGs or metal enrichment → investigate source |

qPCR (ARG panel), ICP-MS for metals |

Bäuerlein et al.29 |

| Agricultural soil | Seasonal (pre/post application) | Particle counts, PHA/PLA fragments, ARGs |

ARG enrichment over baseline → mitigation |

qPCR panel, particle microscopy |

Wilkens et al.30 |

| Sewage treatment plant (STP) | Monthly/per influent batch | Particle load, ARG copies, MGE markers |

ARGs at effluent above regulatory thresholds → action |

qPCR ddPCR for intI1, bla_TEM, qnrS |

Wilkens et al.30 |

| Lists each environment, recommended sampling frequency and the core measurements (e.g., particle counts, leachate chemistry, ARG/MGE qPCR targets). STP: Sewage treatment plant, qPCR: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction, intI1: Class 1 integron integrase, IncP: Incompatibility group P (plasmid). Specifies decision thresholds/action triggers (e.g., ARG >10 copies/g) as presented in the table and accompanying citations | |||||

| Table 10: | Policy and industry actions: Status and recommended measures | |||

| Jurisdiction/Industry | Current rule/policy (summary) | Identified gap | Recommended action(s) | Standards to adopt/reference | Citation(s) |

| EU (example) | EN 13432 for compostability labeling | Standard tests may not reflect real-world fragmentation/leachates |

Require field testing, monitoring for microfragments and ARG endpoints |

EN 13432+plasmid-resolved surveillance guidance |

Yu et al.31 |

| US (FTC/industry) | Green Guides for environmental claims | Lack of mandatory post-market monitoring for biodegradable claims |

Mandatory surveillance, standardized aging tests |

FTC guidance+ ASTM standards |

Shin et al.32 |

| Industry (compostable labeling) | Variable certification schemes | Lack of harmonized label clarity and post-market data |

Harmonize labels, require disclosure of additives and monitoring |

ISO/ASTM/EN harmonization |

Summers et al.33 |

| International standards bodies | Fragmented standards landscape | No unified bioMP/ARG risk standard |

Convene working group to set testing and reporting standards |

ISO working group proposal (example) |

Summers et al.33 |

| Lists jurisdictions or industry practice entries and the current rule/policy text summarized in the table. EU: European union, FTC: Federal trade commission, ASTM: American society for testing and materials, ISO: International organization for standardization and EN 13432 : European standard for compostability. Shows identified gaps and the recommended actions for each jurisdiction/practice with citation | |||||

| Table 11: | Priority research agenda (3-year roadmap) | |||

| Priority (short/medium/long) | Project/title | Methods/core assays | Timeline and resources (est.) | Expected outcome and policy relevance | Citation(s) |

| Short-term (0-12 month) | HGT assays on aged BioMPs | Conjugation assays, qPCR, plating, controlled aging |

Small lab teams, 3-6 month experiments |

Direct evidence of transfer rates, informs immediate risk guidance |

Yu et al.31 |

| Medium-term (1-2 yrs) | Plasmid-resolved environmental surveys |

Long-read metagenomics, plasmid assembly, qPCR |

Moderate funding, multi-site sampling |

Mapping of ARG/plasmid co-occurrence with BioMPs, regulatory thresholds |

Shin et al.32 |

| Long-term (2-3+yrs) | SIP+evolution studies | 13C-SIP, experimental evolution, metagenomics |

Larger program funding, longitudinal sampling |

Mechanistic understanding of selection and gene mobility, policy frameworks for stewardship |

Summers et al.33 |

| Lists priorities (e.g., short-term HGT assays, medium-term plasmid-resolved surveys, long-term SIP+evolution studies), rationale, and methods. HGT: Horizontal gene transfer, SIP: Stable isotope probing, qPCR: quantitative polymerase chain reaction, 13C: Carbon-13 isotope labeling. Provides estimated timeline and resources and the expected outcomes/policy relevance column entries as shown in the table | |||||

Table 10 compares jurisdictional/industry practices, current rules or policies, identified gaps and recommended actions to address BioMP-related ARG risks. Provides actionable policy and industry steps alongside citations.

Research gaps, prioritized experiments and a 3-year roadmap: Addressing BioMP-associated ARG risks requires targeted research spanning laboratory to field scales. In the short term (0-12 months), standardized HGT assays using aged BioMPs and leachates should quantify conjugation, transformation and transduction rates under controlled microcosms, varying temperature, moisture and UV exposure34. Medium-term (12-24 months) work entails plasmid-resolved metagenomic surveys of compost and mariculture sites, integrating long-read sequencing to map ARG-degradative gene co-occurrence and track MGE dynamics in situ. Long-term (24-36 months) projects will deploy stable isotope probing (SIP) coupled with evolutionary experiments in mesocosms to test co-selection: Plastic carbon assimilation by degraders alongside ARG enrichment trajectories33.

Metrics for impact include: (i) Rates of HGT per particle surface area, (ii) Distribution of ARG-degradation gene linkages on MGEs, (iii) Thresholds at which field conditions drive co-selection above background levels and (iv) Efficacy of mitigation measures (e.g., feedstock modifications) in reducing gene transfer. Interdisciplinary consortia combining polymer chemists, microbial ecologists, bioinformaticians and public-health experts will ensure findings translate into design guidelines, regulatory standards and monitored industry practices.

Table 11 sets out a prioritized 3-year research agenda: short-, medium- and long-term projects, methods, timelines/resources and expected policy relevance. Helps translate research priorities into estimated timelines and outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Biodegradable plastics can reduce dependence on conventional polymers, yet this review shows they still generate persistent micro and nanofragments and diverse leachates that require careful evaluation. Field and laboratory evidence indicates that biodegradable microplastics host distinct biofilms and can concentrate antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements, creating conditions that may enhance horizontal gene transfer. Biofilm proximity, oxidative and chemical stress from aged leachates and particle mediated transport act together to increase the likelihood of gene exchange across environmental compartments. Addressing these risks requires harmonized sampling and aging protocols, rigorous characterization of particles and leachates and plasmid resolved molecular workflows as standard practice. A practical research agenda that combines short term horizontal gene transfer assays, medium term plasmid resolved surveys and long term stable isotope and evolution studies can provide the evidence needed for governance. With targeted research and proportional policy measures, biodegradable plastics can be deployed responsibly while minimizing unintended ecological and genetic impacts.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Biodegradable plastics offer important benefits over conventional polymers, but our synthesis shows they can still generate persistent micro- and nanofragments and diverse leachates that may concentrate antibiotic-resistance genes and mobile elements. Mechanistic and observational evidence points to three nonexclusive pathways: Biofilm-mediated conjugation, leachate/ROS-driven transformation competence and particle-mediated plasmid transport that can enhance horizontal gene transfer in environmental microbiomes. Responsible deployment therefore requires harmonized methods, targeted monitoring (including plasmid-resolved metagenomics) and policy measures that explicitly consider particle formation, leachate chemistry and genetic risks alongside end-of-life benefits.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge the colleagues and librarians who assisted with literature searches, source identification and critical readings that substantially improved this review. This manuscript is a synthesis of published studies and secondary sources; we thank the original authors whose work formed the basis of our analysis. We also acknowledge institutional support and constructive feedback from peer reviewers and colleagues that strengthened the review’s clarity and scope.

REFERENCES

- Mhaddolkar, N., T.F. Astrup, A. Tischberger-Aldrian, R. Pomberger and D. Vollprecht, 2024. Challenges and opportunities in managing biodegradable plastic waste: A review. Waste Manage. Res.: J. Sustainable Circ. Econ., 43: 911-934.

- Velasquez, S.T.R., Q. Hu, J. Kramm, V.C. Santin, C. Völker and F.R. Wurm, 2025. Plastics of the future? An interdisciplinary review on biobased and biodegradable polymers: Progress in chemistry, societal views, and environmental implications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 64.

- Wang, C., J. Yu, Y. Lu, D. Hua, X. Wang and X. Zou, 2021. Biodegradable microplastics (BMPs): A new cause for concern? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 28: 66511-66518.

- Piao, Z., A.A.A. Boakye and Y. Yao, 2024. Environmental impacts of biodegradable microplastics. Nat. Chem. Eng., 1: 661-669.

- Payanthoth, N.S., N.N.N. Mut, P. Samanta, G. Li and J. Jung, 2024. A review of biodegradation and formation of biodegradable microplastics in soil and freshwater environments. Appl. Biol. Chem., 67.

- Meereboer, K.W., M. Misra and A.K. Mohanty, 2020. Review of recent advances in the biodegradability of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) bioplastics and their composites. Green Chem., 22: 5519-5558.

- Yao, X., X. Yang, Y. Lu, Y. Qiu and Q. Zeng, 2025. Review of the synthesis and degradation mechanisms of some biodegradable polymers in natural environments. Polymers, 17.

- Abdelmoez, W., I. Dahab, E.M. Ragab, O.A. Abdelsalam and A. Mustafa, 2021. Bio- and oxo-degradable plastics: Insights on facts and challenges. Polym. Adv. Technol., 32: 1981-1996.

- Narancic, T., F. Cerrone, N. Beagan and K.E. O’Connor, 2020. Recent advances in bioplastics: Application and biodegradation. Polymers, 12.

- Lott, C., A. Eich, D. Makarow, B. Unger and M. van Eekert et al., 2021. Half-life of biodegradable plastics in the marine environment depends on material, habitat, and climate zone. Front. Mar. Sci., 8.

- Costa, P. and M. Lackner, 2025. Biodegradable microplastics: Environmental fate and persistence in comparison to micro- and nanoplastics from traditional, non-degradable polymers. Macromol, 5.

- Hu, L., Y. Zhou, Z. Chen, D. Zhang and X. Pan, 2023. Oligomers and monomers from diodegradable plastics: An important but neglected threat to ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol., 57: 9895-9897.

- Dewi, S.K., S.A. Bhat, Y. Wei and F. Li, 2024. Impacts of biodegradable mulch: Benefits, degradation, and residue effects on soil properties and plant growth. Rev. Agric. Sci., 12: 262-280.

- Lee, W.S., J.H. Kim and T.G. Lee, 2024. Certifications and testing methods for biodegradable plastics. Rev. Chem. Eng., 41: 125-146.

- Easton, T., V. Budhiraja, Y. He, Q. Zhang, A. Arora, V. Koutsos and E. Chatzisymeon, 2025. Antibiotic adsorption by microplastics: Effect of weathering, polymer type, size, and shape. Environments, 12.

- Liao, Y.l., C.D. Gan, X. Zhao, X.Y. Du and J.Y. Yang, 2025. Insight into the interactions between microplastics and heavy metals in agricultural soil solution: Adsorption performance influenced by microplastic types. Environ. Sci. Processes Impacts, 27: 2049-2062.

- Qian, Y., L. Huang, P. Yan, X. Wang and Y. Luo, 2024. Biofilms on plastic debris and the microbiome. Microorganisms, 12.

- Moyal, J., P.H. Dave, M. Wu, S. Karimpour, S.K. Brar, H. Zhong and R.W.M. Kwong, 2023. Impacts of biofilm formation on the physicochemical properties and toxicity of microplastics: A concise review. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol., 261.

- MacLean, J., A. Bartholomäus, R. Blukis, S. Liebner and D. Wagner, 2024. Metatranscriptomics of microbial biofilm succession on HDPE foil: Uncovering plastic-degrading potential in soil communities. Environ. Microbiomes, 19.

- Rajput, M., N. Mathur, A. Singh and P. Bhatnagar, 2024. Microplastics aided augmentation of antibiotic resistance in WWTPs: A global concern. Water Air Soil Pollut., 235.

- Liu, Y., L. Liu, X. Wang, M. Shao and Z. Wei et al., 2025. Microplastics enhance the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in mariculture sediments by enriching host bacteria and promoting horizontal gene transfer. Eco-Environ. Health, 4.

- Abe, K., N. Nomura and S. Suzuki, 2020. Biofilms: Hot spots of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in aquatic environments, with a focus on a new HGT mechanism. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 96.

- Lin, C., L.J. Li, K. Yang, J.Y. Xu, X.T. Fan, Q.L. Chen and Y.G. Zhu, 2025. Protozoa-enhanced conjugation frequency alters the dissemination of soil antibiotic resistance. ISME J., 19.

- Lu, H., Y. Wang, H. Liu, N. Wang, Y. Zhang and X. Li, 2025. Review of the presence and phage-mediated transfer of ARGs in biofilms. Microorganisms, 13.

- Mohanan, N., Z. Montazer, P.K. Sharma and D.B. Levin, 2020. Microbial and enzymatic degradation of synthetic plastics. Front. Microbiol., 11.

- Salini, A., L. Zuliani, P.M. Gonnelli, M. Orlando and A. Odoardo et al., 2024. Plastic-degrading microbial consortia from a wastewater treatment plant. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 25.

- Tantawi, O., W. Joo, E.E. Martin, S.H.M. Av-Ron and K.R. Bannister et al., 2025. Designing for degradation: The importance of considering biotic and abiotic polymer degradation. Environ. Sci. Processes Impacts, 27: 1303-1316.

- Bocci, V., S. Galafassi, C. Levantesi, S. Crognale and S. Amalfitano et al., 2024. Freshwater plastisphere: A review on biodiversity, risks, and biodegradation potential with implications for the aquatic ecosystem health. Front. Microbiol., 15.

- Bäuerlein, P.S., M.W. Erich, W.M.G.M. van Loon, S.M. Mintenig and A.A. Koelmans, 2024. A monitoring and data analysis method for microplastics in marine sediments. Mar. Environ. Res., 15.

- Wilkens, J.L., A.J. Calomeni-Eck, J. Boyda, A. Kennedy and A.D. McQueen, 2024. Microplastic in dredged sediments: From databases to strategic responses. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol., 112.

- Yu, Y. and M. Flury, 2024. Unlocking the potentials of biodegradable plastics with proper management and evaluation at environmentally relevant concentrations. npj Mater. Sustainability, 2.

- Shin, G., S.A. Park, J.M. Koo, M. Kim and M. Lee et al., 2021. A micro-spray-based high-throughput screening system for bioplastic-degrading microorganisms. Green Chem., 23: 5429-5436.

- Summers, S., M. Sufian Bin-Hudari, C. Magill, T. Henry and T. Gutierrez, 2024. Identification of the bacterial community that degrades phenanthrene sorbed to polystyrene nanoplastics using DNA-based stable isotope probing. Sci. Rep., 14.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Anih,

D.C., Dorothy,

A.C., Linus,

E.N., Oyibo,

O.N., Olaitan,

S.L., Ibiang,

G.A., Tarshi,

M.W., Ugwuoke,

K.C. (2026). Biodegradable Plastics and Microbial Gene Dynamics: Risks of Particle Formation, Leachates and Gene Dissemination. Trends in Environmental Sciences, 2(1), 13-27. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.13.27

ACS Style

Anih,

D.C.; Dorothy,

A.C.; Linus,

E.N.; Oyibo,

O.N.; Olaitan,

S.L.; Ibiang,

G.A.; Tarshi,

M.W.; Ugwuoke,

K.C. Biodegradable Plastics and Microbial Gene Dynamics: Risks of Particle Formation, Leachates and Gene Dissemination. Trends Env. Sci 2026, 2, 13-27. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.13.27

AMA Style

Anih

DC, Dorothy

AC, Linus

EN, Oyibo

ON, Olaitan

SL, Ibiang

GA, Tarshi

MW, Ugwuoke

KC. Biodegradable Plastics and Microbial Gene Dynamics: Risks of Particle Formation, Leachates and Gene Dissemination. Trends in Environmental Sciences. 2026; 2(1): 13-27. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.13.27

Chicago/Turabian Style

Anih, David, Chinonso, Asogwa, Chikaodili Dorothy, Emmanuel Ndirmbula Linus, Okpanachi Nuhu Oyibo, Sulaiman Luqman Olaitan, Gabriel Arikpo Ibiang, Monday William Tarshi, and Kenneth Chinekwu Ugwuoke.

2026. "Biodegradable Plastics and Microbial Gene Dynamics: Risks of Particle Formation, Leachates and Gene Dissemination" Trends in Environmental Sciences 2, no. 1: 13-27. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.13.27

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.