Triangulation in Ecological Research: Epistemological Roots, Field Realities, and Integrative Pathways

| Received 31 Oct, 2025 |

Accepted 01 Feb, 2026 |

Published 31 Mar, 2026 |

Ecological research is increasingly engaging with systems characterized by uncertainty, nonlinearity, and cross-scale interactions. In this context, triangulation, which is the deliberate integration of multiple methods, datasets, and epistemic standpoints, has re-emerged as a strategy for strengthening ecological inference and enhancing interpretive depth. This paper reframes triangulation as an epistemological framework rather than a technical procedure. It traces its conceptual trajectory from early positivist notions of verification to contemporary pluralist approaches that value uncertainty, contradiction, and situated knowledge. Building on recent theoretical and empirical advances, the study proposes a three-tiered model of ecological triangulation encompassing empirical corroboration, interpretive complementarity, and reflexive integration. Each dimension contributes to methodological rigour, contextual sensitivity, and epistemic inclusivity. However, persistent institutional and structural barriers such as short funding cycles, disciplinary silos, and the privileging of quantitative uniformity limit its broader adoption. The paper argues that ecological science must institutionalise pluralism through new funding, training, publishing, and policy mechanisms. Integrative triangulation, underpinned by ethical reflexivity and co-production, reconciles technological precision with local and Indigenous knowledge systems. In doing so, it provides a normative foundation for equitable, credible, and adaptive ecological research in the Anthropocene.

| Copyright © 2026 Jacob et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

The study of ecology has evolved into a science of complexity, being one that thrives on patterns, interconnections, and dynamic uncertainty1. Unlike laboratory disciplines where variables can be tightly controlled, ecological inquiry operates within open systems marked by variability across temporal, spatial, and biological scales. As environmental challenges become increasingly intertwined with human processes, researchers have recognised the limitations of single-method approaches in generating valid, holistic knowledge2. Within this context, triangulation, which is the strategic combination of multiple data sources, analytical procedures, and interpretative perspectives, has emerged as a robust paradigm for reinforcing reliability and expanding understanding in ecological research3. At its core, triangulation seeks

to address a fundamental problem in ecology: How can truth be discerned when the subject of study continually changes? The answer lies not in choosing a single method deemed “best,” but in weaving together diverse lenses that collectively approximate ecological reality. Dobson et al.4 argued that triangulation balances methodological subjectivity and empirical precision, fostering a more stable interpretation of complex phenomena. In ecological contexts, this means combining biophysical measurements with ethnographic observation, statistical modelling with participatory mapping, and remote sensing with field surveys. Each strand offers partial insight; together they form a fabric of evidential strength.

Historically, the philosophy of triangulation grew from the social sciences but found fertile ground in ecology when environmental monitoring began to demand both quantitative accuracy and contextual relevance. Early wildlife studies, for instance, relied primarily on direct observation or capture–recapture models, yet these approaches often produced divergent estimates of species abundance. Researchers soon realised that integrating independent measures such as acoustic monitoring, camera trapping, and genetic sampling yielded more credible population assessments5. This methodological convergence mirrored an epistemological shift: Truth in ecology could no longer be claimed by a single instrument but by the corroboration of difference. The significance of triangulation also extends beyond data validation. It represents a philosophical resistance to reductionism and an embrace of epistemic pluralism. Lindenmayer and Likens6 highlight that ecological systems are inherently multi-scalar; understanding them requires a dialogue between competing explanations rather than a search for singular certainty. Triangulation thus emerges as a reconciliatory practice as one that unites empirical observation with interpretive understanding, linking what is measured to what is lived and experienced. It acknowledges that every observation is situated within uncertainty, and that strength emerges from synthesis rather than uniformity.

In practical research design, triangulation enriches both internal and external validity. Internally, it cross-verifies findings through alternative techniques such as comparing sensor-based climate data with field-based observations or integrating macroecological modelling with site-level ground truthing7. Externally, it enhances transferability across contexts by combining biophysical evidence with local ecological knowledge. This multidimensional reliability fosters policy relevance, especially where conservation outcomes depend on reconciling scientific data with community perceptions8. Ecology’s transition into the Anthropocene era has further amplified the need for triangulated inquiry. Environmental problems such as biodiversity loss, climate-induced migration, and landscape degradation now occur at scales that exceed traditional disciplinary and methodological boundaries. The integration of remote sensing, citizen science, and machine learning exemplifies the growing hybridity of ecological research9. Yet these innovations also reintroduce epistemic challenges: Data saturation, interpretive conflict, and the risk of false precision. Triangulation thus functions as both a safeguard and a framework, and it disciplines methodological expansion while preserving interpretive coherence. Despite its promise, triangulation in ecology remains under-theorised. Many studies apply multiple methods without a clear logic of integration, reducing triangulation to a checklist of techniques rather than a coherent epistemic strategy. This paper, therefore, repositions triangulation as a system of reasoning, a structured pathway linking philosophy, method, and application. By examining its epistemological roots, methodological forms, and practical relevance, the study seeks to articulate a comprehensive model of how triangulation operates within ecological science.

EPISTEMOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF TRIANGULATION IN ECOLOGY

Evolution of triangulation: Triangulation’s intellectual roots trace back to the post-positivist turn in the mid-twentieth century, particularly in psychology and the social sciences. Campbell and Fiske’s multitrait–multimethod matrix first formalized triangulation as a test of convergent validity, arguing that if independent methods yielded consistent results, the construct under investigation was likely genuine.

This early conception reflected a realist epistemology: The world exists independently of our observations, and multiple methods can converge toward its true description10. Within this framework, triangulation served as a scientific safeguard, that is an epistemic insurance against the biases of single-method dependence2. Later, Denzin11 expanded triangulation beyond psychometrics, identifying four forms, namely, data, investigator, theoretical, and methodological triangulation, and relocating the practice into interpretivist traditions. This shift redefined triangulation from a purely validation-oriented procedure to one concerned with epistemic breadth, reflexivity, and the interrogation of meaning. The conceptual expansion carried an implicit epistemological pluralism that methods are not just tools to locate truth, but diverse lenses revealing different facets of reality12. Denzin’s framework emphasized the dialogue among perspectives rather than their synthesis, implying that understanding emerges through negotiated meanings rather than empirical convergence.

In ecology, these epistemic commitments proved particularly salient. Ecological systems are complex, nonlinear, and multi-scalar; thus, no single method can adequately describe their dynamics13. As such, triangulation was appropriated not simply as a method of verification, but as an ontological necessity, a response to the reality that ecological phenomena manifest differently across space, scale, and observer. This recontextualization paralleled the rise of systems ecology and resilience theory, which foregrounded feedback, uncertainty, and emergent properties14. Triangulation, therefore, became a way of aligning epistemology with ecology’s ontological complexity: Recognizing that knowledge about ecosystems is partial, situated, and contingent upon methodological framing. In addition, contemporary ecological epistemology increasingly views triangulation as a mechanism for embracing rather than resolving uncertainty15. Rather than assuming convergence among data sources, ecological triangulation accepts that different methods might yield contradictory insights that together enrich understanding. For example, combining remote sensing with ethnographic or participatory methods often exposes discrepancies between biophysical metrics and local perceptions of change16. Such dissonance, rather than being an error to correct, becomes epistemically productive as it forces reflection on whose knowledge counts and under what conditions ecological claims hold validity. In this sense, triangulation operates as both an epistemic and ethical stance, recognizing that the complexity of nature necessitates an equally complex epistemology.

This orientation also aligns with the critical realist turn in environmental research, which reconciles ontological realism with epistemological relativism. Under this paradigm, the ecological world exists independently of observers, yet our access to it is mediated by methods, perspectives, and values. Triangulation, therefore, is not a quest for certainty but an acknowledgment of the layered nature of ecological knowledge comprising empirical, interpretive, and normative knowledge. It is a methodological expression of epistemic humility17. Table 1 below summarizes the epistemological evolution of triangulation from positivist to post-positivist to pluralist frameworks, illustrating its increasing relevance to ecological inquiry. This historical trajectory shows how triangulation evolved from an instrument of epistemic closure to one of epistemic openness, a movement from seeking certainty to embracing complexity. In ecology, this shift has been transformative as it reframes the act of knowing nature as a plural and adaptive process rather than a singular discovery of facts.

| Table 1: | Evolution of triangulation and its epistemological orientation | |||

| Era/paradigm | Disciplinary context | Epistemic assumption | Purpose of triangulation |

| 1950s-1960s (Positivist) | Psychology, Social Sciences |

Objective reality exists; observation can approximate truth |

Validation and verification |

| 1970s-1990s (Post-Positivist/ Interpretivist) |

Sociology, Anthropology |

Multiple realities; knowledge is constructed |

Enrich interpretation through multiple perspectives |

| 2000s-Present (Critical Realist/ Pluralist) |

Ecology, Sustainability Science |

Reality is complex, stratified, and context-dependent |

Integrate diverse knowledge systems and scales |

|

|

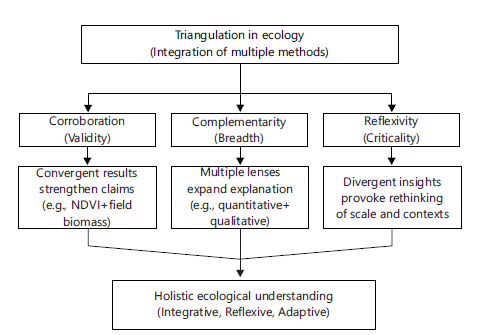

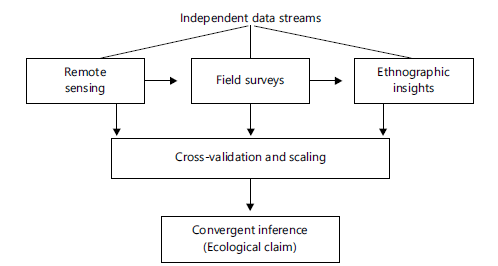

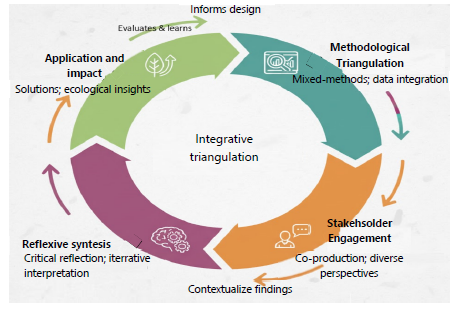

Triangulation in ecological inquiry: Triangulation in ecological inquiry embodies a philosophical and methodological strategy aimed at reconciling the epistemic diversity of environmental knowledge systems. It is not simply a means of validating results but a framework for expanding understanding and cultivating reflexivity about how knowledge is produced and justified in complex ecological contexts. As Dawadi et al.18 observe, triangulation performs three intertwined epistemic functions of corroboration, complementarity, and reflexivity, with each corresponding to a distinct mode of engaging with ecological complexity. These functions collectively transform triangulation from a statistical tool into an ecological epistemology: One that situates data, context, and interpretation within an evolving dialogue between observation and understanding (Fig. 1).

Corroboration: In ecology, corroboration through triangulation reflects the principle that independent methods or data sources can jointly enhance the credibility of scientific claims. When remote-sensing data, field-based ecological measurements, and local knowledge converge, the resulting inferences gain not only empirical support but also contextual depth19. For instance, vegetation regrowth observed via the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) can be cross-validated with field biomass sampling and interviews with community members about seasonal land-use patterns. This methodological convergence mitigates the limitations inherent in any single data type, whether satellite bias, sampling error, or observer subjectivity, and enhances the robustness of ecological interpretation20. In this sense, triangulation

operates as a hedge against epistemic vulnerability. Complex systems often yield incomplete or noisy data, and single-method studies risk mischaracterizing ecological dynamics. Triangulation, therefore, reinforces inference reliability by aligning multiple pathways of evidence toward a shared conclusion. Yet, corroboration in ecology extends beyond the positivist notion of replication. It encompasses scale integration, which is testing whether patterns observed at the micro-level (e.g., soil nutrient dynamics) correspond to macro-level phenomena (e.g., vegetation productivity). For example, Dronova et al.21 demonstrated that triangulating drone-based imagery, ground spectral readings, and vegetation transects provided a more accurate estimation of wetland recovery following restoration efforts, revealing how method integration reinforces ecological inference.

The value of corroboration lies not only in empirical strength but also in epistemic diversity. Each method embodies a partial lens; when multiple lenses overlap, they illuminate shared structural patterns that may indicate underlying causal mechanisms. Figure 2 illustrates this process of ecological corroboration through convergence, showing how distinct data streams integrate within a triangulated inference framework. This multi-source approach is now central to integrative ecological monitoring programs. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), for instance, routinely employs triangulated data by combining citizen science observations, satellite imaging, and taxonomic surveys to refine biodiversity models and detect spatial biases22. The epistemic lesson is profound: triangulation does not merely add data but reorganizes how evidence itself is conceptualized in relation to ecological truth.

Complementarity: While corroboration seeks convergence, complementarity emphasizes divergence as enrichment, and each method contributes unique dimensions of ecological meaning. Ecological systems cannot be captured by a single epistemic lens because their phenomena are emergent, multi-scalar, and context-dependent. Complementarity allows researchers to integrate qualitative and quantitative perspectives without forcing them into an artificial unity23. Quantitative models may reveal what is changing, while qualitative or participatory inquiries illuminate why and how such change occurs. For example, in community-based forest management studies, remote sensing quantifies canopy cover loss or regeneration, while ethnographic interviews explain the socio-political motivations behind land-use decisions. The combination produces a richer, multidimensional understanding of ecological processes that transcends disciplinary boundaries. Similarly, integrating species distribution models with indigenous ecological knowledge (IEK) enables researchers to capture environmental knowledge that standard models often overlook19,24. Such complementarity transforms triangulation from a method of verification into a hermeneutic strategy, a way of weaving together quantitative regularities and qualitative particularities to construct holistic ecological narratives.

Complementarity is also crucial for addressing the epistemic asymmetry between scientific and local knowledge systems. Conventional ecological science privileges numerical precision, while traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) values experiential and contextual insight25. Triangulation allows these epistemic traditions to coexist and inform each other. The outcome is not a homogenized dataset but a dialogical synthesis in which each perspective maintains integrity while contributing to a broader ecological mosaic. Table 2 exemplifies how complementary methods can be strategically combined in ecological research to generate integrated, contextually sensitive insights. The integrative potential of complementarity, therefore, underscores the evolving nature of ecological epistemology from unidimensional observation to multi-perspectival understanding. As Vogl et al.12 note, such epistemic pluralism allows triangulation to act as a “bridge method,” enabling scientists to transcend methodological isolation and engage more inclusively with the multiplicity of ecological realities.

Reflexivity: Reflexivity represents the most critical and transformative dimension of triangulation in ecological research. While corroboration strengthens validity and complementarity broadens understanding, reflexivity deepens self-awareness about the limits, assumptions, and positionalities

|

| Table 2: | Applications of complementarity in ecological triangulation | |||

| Ecological context | Quantitative component | Qualitative/contextual component |

Integrated insight |

| Forest regeneration assessment | NDVI, LiDAR biomass data | Farmer narratives on planting cycles |

Validates regeneration trends with social adaptation factors |

| Wetland restoration monitoring | Hydrological modeling | Community mapping of flood patterns |

Identifies socio-hydrological feedbacks |

| Climate adaptation studies | Species abundance trends | Local climate perception surveys |

Aligns biophysical impacts with adaptive strategies |

| Soil degradation analysis | Carbon flux measurement | Indigenous soil classification |

Reveals context-specific degradation thresholds |

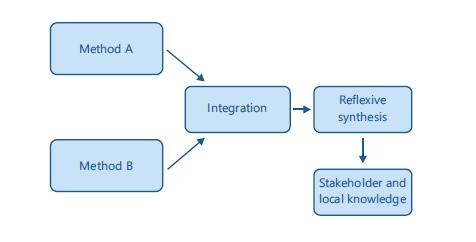

embedded within research practice26. In ecological triangulation, reflexivity entails acknowledging that divergent results are not mere methodological failures but potential indicators of new ecological or social insights12. For instance, when spatial data from satellite imagery contradict field reports of biodiversity abundance, the discrepancy may reflect differences in temporal resolution, measurement scales, or socio-perceptual interpretations25. Rather than dismissing such conflicts, reflexive triangulation seeks to interrogate them by asking whether the divergence reveals hidden ecological dynamics (such as migration timing) or exposes socio-epistemic biases (such as observer expectations). This approach aligns with critical realism, where contradictions between data sources are seen as opportunities to uncover deeper generative mechanisms rather than inconsistencies to be eliminated. Reflexivity also has an ethical dimension: It demands that ecologists remain cognizant of how their positionality, disciplinary training, and institutional frameworks influence data interpretation. In participatory ecological assessments, reflexivity ensures that community voices are not instrumentalized as mere data points but engaged as epistemic partners in knowledge production27. This reorientation moves triangulation from an instrumental tool toward an ethical methodology that values transparency, humility, and accountability. Figure 3 illustrates the reflexive cycle of triangulation, emphasizing how divergence among data sources can catalyze iterative refinement in ecological understanding. This reflexive loop mirrors the adaptive nature of ecological systems themselves. Just as ecosystems self-organize through feedback, ecological knowledge evolves through reflexive feedback among methods, perspectives, and interpretations28. Reflexivity thus transforms triangulation into a learning system, one capable of adapting its epistemic architecture in response to new forms of evidence. Thus, triangulation’s reflexive dimension serves as both a philosophical stance and a methodological practice. It redefines ecological inquiry as an evolving dialogue between data and meaning, between observation and reflection. By treating divergence as discovery, triangulation becomes an epistemic compass guiding researchers through the uncertain terrain of ecological complexity where truth is provisional, multi-perspectival, and dynamically co-constructed.

| Table 3: | Practical challenges of triangulation in ecology | |||

| Challenge | Implication for ecological research |

| Non-independence of data sources | Spurious convergence, overconfidence in results |

| Assumed single ontology | Neglect of socio-cultural and local perspectives |

| Lack of integration criteria | Ambiguous synthesis, selective use of evidence |

| Epistemic inequity | Marginalization of indigenous/local knowledge systems |

Challenges and ethical dimensions: Despite its promise, triangulation in ecological research is not free from limitations. Epistemic independence, ontological multiplicity, and ethical reflexivity represent persistent challenges that determine whether triangulation yields epistemic strength or methodological confusion. These limits arise from ecology’s interdisciplinary character, that is its dependence on both quantitative precision and qualitative interpretation, and its deep entanglement with political and cultural realities (Table 3).

Assumption of independence: The credibility of triangulation depends on the independence of the data streams used. Yet, genuine independence in ecological research is often elusive. Field data, remote-sensing outputs, and modelled predictions frequently share overlapping assumptions or calibration parameters29. When field measurements used to train satellite-based vegetation models are later compared to those same models for validation, the apparent agreement may represent circular reasoning rather than independent corroboration. This pseudo-independence undermines the inferential robustness that triangulation claims to provide. Moreover, the assumption of independence often ignores institutional and cognitive dependencies within research teams. Scholars working within shared paradigms or funding frameworks may unconsciously align interpretations, producing what Bloor30 calls epistemic homogeneity, which is a convergence of conclusions shaped more by social consensus than empirical truth. In ecological monitoring networks such as Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network (GEO BON) or International Long Term Ecological Research Network (ILTERNET), shared protocols, while enhancing comparability, can unintentionally constrain epistemic diversity. To mitigate these biases, researchers must design triangulated studies that deliberately diversify not only data sources but also analytical frameworks and investigator perspectives. Reflexive transparency in data provenance and independence metrics now advocated in open science standards should thus become integral to ecological triangulation.

Ontological multiplicity: Triangulation historically assumes that diverse methods, when applied rigorously, should converge toward a single, objective ecological reality. However, ecology’s subject matter defies such reductionism. Ecosystems are dynamic, emergent, and multi-scalar meaning that phenomena whose properties vary depending on the lens of observation12. Ontological multiplicity, which is the coexistence of different but valid realities within ecological systems renders total convergence both philosophically and practically untenable. For example, coral reef degradation can be simultaneously understood as a biochemical process (loss of calcium carbonate), a socio-economic collapse (loss of livelihoods), and a spiritual dislocation (loss of ancestral meaning). Each represents a distinct ontology grounded in unique epistemic traditions. Demanding their convergence under a single explanatory model risks epistemic violence by silencing non-Western and indigenous ways of knowing. As a study by Dion et al.31 argue, true ecological understanding demands ontological openness a willingness to accept that different knowledge systems describe not competing versions of the same world, but different worlds altogether. Triangulation, therefore, must evolve from being an instrument of validation to a practice of epistemic diplomacy, negotiating between disparate realities without forcing their synthesis. Mixed-method frameworks like multiple evidence base (MEB) approaches embody this philosophy by allowing parallel validity of scientific and local knowledge claims. Ecological triangulation becomes strongest not when it collapses diversity into unity, but when it sustains respectful coexistence among plural truths.

Integration and weighting problem: Once multiple data streams have been collected, the challenge shifts from acquisition to integration. How should findings from remote sensing, ethnographic interviews, and ecological modelling be synthesized? The problem is not merely technical as it is epistemological.

Different data types encode different assumptions about what counts as evidence18. A statistical model’s strength lies in its precision and generalizability, while ethnographic narratives offer contextual richness and meaning. Yet, when forced into a single analytical framework, one often dominates the other, creating epistemic imbalance. Integration requires explicit, theory-driven weighting schemes. For instance, Bayesian synthesis techniques allow probabilistic reconciliation of heterogeneous datasets, while participatory modelling incorporates stakeholder values into model structures31. However, such approaches are only effective when accompanied by reflexive transparency about the criteria guiding inclusion and weighting. Without this, triangulation risks devolving into confirmation triangulation, that is a process where only data supporting pre-existing hypotheses are emphasized. Additionally, the temporal and spatial scales of datasets often differ drastically: While satellite imagery captures large-scale patterns, ethnographic or field data are localized and episodic. This mismatch can distort interpretation unless explicitly modeled. Therefore, integration in ecological triangulation is not an end-state but an iterative negotiation. It is an evolving dialogue between precision and meaning, evidence and experience. Methodological pluralism must therefore be matched by interpretive pluralism, to ensure that triangulated synthesis respects both empirical robustness and epistemic diversity.

Ethical and political dimensions: Triangulation, though often presented as a neutral methodological choice, is inherently political. It shapes which voices are amplified and which are marginalized in ecological research. When technologically mediated data such as satellite observations or AI-driven models are prioritized over Indigenous ecological knowledge (IEK), it perpetuates what Ndlovu-Gatsheni32 calls methodological imperialism. This hierarchy not only undermines data justice but erases epistemic agency from communities most affected by ecological degradation. Ethical triangulation demands co-production of knowledge through inclusive design and interpretation. Participatory triangulation, wherein local communities define research questions, data priorities, and validation criteria, democratizes ecological inquiry and enhances legitimacy25. Moreover, ethical reflexivity requires that researchers interrogate their own positionality, their social, cultural, and institutional contexts that shape how data are interpreted. A practical example lies in wildlife management, where integrating camera-trap data with Indigenous tracking knowledge has improved biodiversity assessment accuracy and community stewardship. Here, triangulation becomes not just a methodological technique but a moral commitment to equity and mutual learning. Thus, the future of ecological triangulation lies in its ethical evolution from a quest for objectivity to a relational practice grounded in respect, transparency, and shared authorship.

METHODOLOGICAL FORMS OF TRIANGULATION IN ECOLOGICAL RESEARCH

Triangulation, as a methodological philosophy, is founded on the epistemic conviction that reality, particularly ecological reality can only be partially grasped through any single methodological lens. In ecology, this conviction translates into methodological pluralism that combines quantitative precision with qualitative richness, and integrates biophysical observation with socio-cultural interpretation. The methodological forms of triangulation which are data, investigator, theoretical, and methodological were first codified by Denzin11 and have since evolved through interdisciplinary adaptation. In contemporary ecological research, these forms no longer exist as discrete categories but as interwoven strategies that collectively aim to capture the multidimensional nature of ecosystems and their human entanglements. These forms are consolidated into three interrelated domains of empirical triangulation, interpretive triangulation, and integrative triangulation, with each one of them representing a progressive deepening of methodological synthesis.

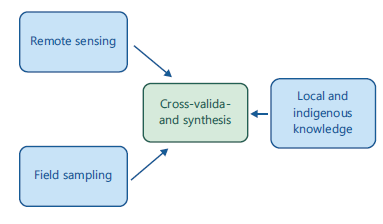

Empirical triangulation: Empirical triangulation lies at the foundation of ecological inquiry. It refers to the use of multiple data sources and investigators to enhance the credibility and reliability of findings (Fig. 4). In practice, this form of triangulation acknowledges that no single dataset or researcher perspective can capture the full complexity of ecological systems, which are inherently spatially heterogeneous, temporally dynamic, and shaped by human perception. Data triangulation in ecology has

|

| Table 4: | Forms and purposes of interpretive triangulation in ecology | |||

| Triangulation form | Operational Approach | Epistemic Purpose | Example application |

| Theoretical triangulation |

Multiple frameworks interpreting a phenomenon |

Deepens causal and contextual understanding |

Combining resilience theory and political ecology in coral reef studies |

| Methodological triangulation |

Combining qualitative and quantitative methods |

Expands explanatory range and system comprehension |

Integrating satellite data with ethnographic interviews on land-use change |

| Reflexive triangulation |

Interrogating researcher assumptions and positionality |

Enhances interpretive validity and ethical rigor |

Participatory environmental assessment involving local and scientific actors |

been revolutionized by technological advances that enable multi-scalar observation. Satellite-based Earth observation systems, long-term field plots, and citizen science platforms together produce overlapping yet distinct perspectives on biodiversity, vegetation dynamics, and ecosystem services. For example, vegetation recovery following deforestation can be tracked using a combination of NDVI data, local biomass sampling, and community interviews. While NDVI provides synoptic temporal trends, field data validate species-level composition, and local narratives contextualize observed changes in terms of livelihood and policy decisions13. Such multi-source convergence enhances empirical robustness by cross-verifying observations through independent yet complementary channels.

However, investigator triangulation extends beyond datasets to the people generating them. By involving multiple researchers from different disciplinary, cultural, or institutional backgrounds, ecological teams reduce the risk of interpretive bias30. For instance, collaborative studies combining ecologists, social anthropologists, and GIS analysts yield interpretations that account for both biophysical dynamics and social drivers. In transboundary biodiversity monitoring initiatives, such as the GEO BON and ILTERNET, investigator triangulation fosters intercultural interpretation of ecological data33. These collaborations exemplify a mode of scientific production grounded in mutual reflexivity and the negotiation of meaning. Nonetheless, empirical triangulation faces a persistent challenge of ensuring independence among datasets and perspectives. Overlapping data collection protocols and shared analytical assumptions can generate pseudo-convergence, masking errors as validation. Thus, robust empirical triangulation demands transparency in data provenance and reflexive documentation of interpretive assumptions. Open data platforms, reproducibility standards, and inter-laboratory cross-checks represent emerging institutional responses to this challenge. Consequently, empirical triangulation enhances inferential reliability. It grounds ecological findings in a broader evidential base and allows independent streams of observation to converge or constructively diverge around the same phenomenon. Such multi-perspectival convergence offers an empirical buffer against uncertainty, a virtue indispensable in complex systems science.

Interpretive triangulation: Interpretive triangulation represents a higher-order form of synthesis, in which theoretical and methodological diversity are harnessed to deepen explanatory understanding (Table 4). Unlike empirical triangulation which is concerned with validating what is, interpretive

riangulation seeks to explain why and how ecological phenomena manifest. It thrives at the intersection of paradigms, translating between quantitative empiricism and qualitative interpretation18. Theoretical triangulation involves applying multiple conceptual frameworks to interpret the same ecological event. For example, coral bleaching may be understood simultaneously through the lens of climate stress physiology, resilience theory, and political ecology. Each framework illuminates different causal dimensions: physiological stress responses, ecosystem recovery thresholds, and human governance structures respectively. The aim is not to reconcile these frameworks into a single meta-theory but to explore the intersections and tensions among them. This pluralistic reasoning reflects post-normal science, where uncertainties, value conflicts, and stakeholder perspectives shape both problem framing and solution design.

Methodological triangulation, closely aligned with this theoretical pluralism, combines different research methods such as quantitative, qualitative, and participatory methods to reveal complementary dimensions of ecological processes34. For example, integrating ecological modelling, ethnographic fieldwork, and participatory mapping provides a fuller understanding of land-use change. Quantitative spatial models capture deforestation rates, qualitative narratives explain farmer decision-making, and participatory maps visualize local perceptions of environmental change. Such integration exemplifies what Andrada35 describe as epistemic complementarity, which is the use of multiple methods to uncover different facets of a system that no single approach could independently reveal. Interpretive triangulation, however, requires reflexivity or an awareness that methods are not neutral instruments but interpretive lenses shaped by the researcher’s worldview. This reflexivity demands deliberate negotiation between commensurability and incommensurability among knowledge systems. For instance, remote sensing may quantify land degradation through spectral signatures, whereas Indigenous knowledge systems interpret the same landscape through narrative and spiritual indicators. Rather than forcing equivalence, interpretive triangulation recognizes that both perspectives hold partial truths about the ecosystem. This interpretive synthesis transforms triangulation from a validation technique into an epistemic dialogue. It facilitates the co-construction of meaning across disciplines and knowledge systems, thereby enriching ecological interpretation. The resultant outcome is not uniform agreement but reflexive coherence: a dynamic, multi-perspective understanding of ecological phenomena.

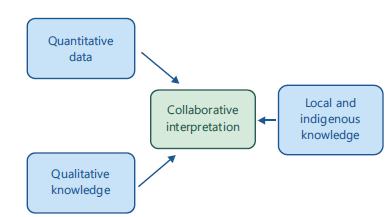

Integrative triangulation: Integrative triangulation represents the most mature and demanding form of methodological synthesis. It transcends empirical and interpretive triangulation by embedding them within transdisciplinary frameworks of knowledge co-production (Fig. 5). Here, triangulation is not merely about combining datasets or theories; it is about integrating knowledge systems, institutional practices, and value frameworks into a coherent process of ecological inquiry25. In this sense, integrative triangulation aligns with the co-production paradigm, which treats stakeholders comprising scientists, policymakers, Indigenous custodians, and communities as co-researchers rather than data providers. The process entails iterative cycles of observation, interpretation, and feedback, wherein each actor contributes unique epistemic resources. This inclusive framework acknowledges that knowledge is situated, socially mediated, and ethically charged. For example, in participatory climate adaptation projects in East Africa, blending meteorological data, hydrological models, and pastoralist knowledge has produced more resilient adaptation strategies than science-led models alone25.

Integrative triangulation also embodies epistemic humility, that is the recognition that all knowledge systems are partial and that synthesis requires negotiation rather than domination. The emphasis shifts from consensus to reflexive synthesis, where conflicting insights are treated as opportunities for conceptual expansion. This form of triangulation is increasingly supported by computational tools such as Bayesian hierarchical integration, ensemble modelling, and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), which allow systematic weighting and reconciliation of heterogeneous evidence streams36. However,

|

| Table 5: | Quantitative and qualitative dimensions of ecological triangulation | |||

| Research area | Triangulated elements | Methodological outcome |

| Carbon sequestration | Allometric data, LiDAR canopy metrics, NDVI indices | Reduced estimation bias and enhanced cross-scale validity |

| Biodiversity assessment | eDNA analysis, camera trapping, acoustic monitoring | Comprehensive detection of cryptic species |

| Socio-ecological resilience | Climate models, community interviews, livelihood data | Grounded adaptation strategies |

| Wetland management | Hydrological datasets, participatory mapping, TEK | Integrative ecosystem governance |

integration is not merely technical but ethical. Without equitable participation, triangulation risks reinforcing epistemic hierarchies, where scientific methods override Indigenous or experiential knowledges. Ethical integrative triangulation, therefore, demands procedural fairness, ensuring that power, authorship, and benefit-sharing are distributed justly among knowledge contributors.

In ecological governance, integrative triangulation underpins adaptive management which is a cyclical process of learning, feedback, and revision. For example, in community-based fisheries management, triangulating stock assessment data, fisher narratives, and ecological modelling has generated more adaptive and culturally sensitive policies. Such synthesis bridges the science-policy divide and transforms triangulation into a vehicle for transformative knowledge, knowledge capable of altering both understanding and practice. Ultimately, integrative triangulation exemplifies the epistemic maturity of ecology as a post-normal science: Plural, reflexive, and ethically attuned. It operationalizes the idea that knowledge is not discovered but constructed through dialogic engagement among diverse ways of knowing. As environmental crises deepen in scale and complexity, such transdisciplinary triangulation offers a pathway toward sustainable understanding and just ecological futures.

APPLICATIONS IN ECOLOGICAL RESEARCH

Integrated dimensions of ecological triangulation: In ecological research, triangulation operates as a methodological compass that aligns multiple pathways of knowing toward a shared interpretive horizon (Table 5). The intrinsic complexity of ecological systems marked by nonlinearity, scale dependence, and emergent dynamics demands an approach that is simultaneously empirical, interpretive, and reflexive13. Within this epistemic terrain, triangulation functions not merely as a strategy for validation but as a mechanism of ecological synthesis, merging diverse evidence streams into an adaptive and integrative framework of understanding. Historically, quantitative triangulation in ecology has provided the empirical scaffolding for model calibration and data validation. For instance, species distribution models (SDMs) that predict the potential range of organisms under changing climatic conditions are often triangulated with in-situ occurrence data, remote-sensing vegetation indices, and long-term climatic datasets. This integrative practice enhances the predictive power and ecological realism of such models37. Similarly, in

| Table 6: | Applied domains of ecological triangulation | |||

| Domain | Triangulated dimensions | Key benefit |

| Biodiversity monitoring | eDNA, acoustic data, field surveys | Multiscale species detection |

| Ecosystem service valuation | Biophysical, economic, and cultural data | Holistic value frameworks |

| Climate adaptation | Climate models, local knowledge, phenology | Contextual adaptation pathways |

| Hydrological management | Remote sensing, field data, participatory input | Reflexive water governance |

tropical forest ecology, carbon sequestration estimates derived from allometric equations are cross-validated using LiDAR-based canopy structure analysis and satellite imagery such as MODIS NDVI. The triangulation of these independent datasets minimizes bias, particularly that arising from canopy saturation or spectral reflectance variability. However, triangulation’s power extends beyond numeric precision.

In socio-ecological contexts, qualitative and participatory triangulation bridge the gap between ecological science and the lived experiences of local communities. For example, in the wetlands floodplain, integrating hydrological data with fisherfolk narratives and participatory mapping elucidates how ecological degradation correlates with local livelihood transformations Flick38. Such integration situates ecological patterns within social and cultural matrices, revealing how community perceptions shape adaptive responses. This qualitative triangulation complements quantitative measures, ensuring that ecological knowledge reflects both empirical and experiential truths. The same principle applies to theoretical triangulation, which interweaves conceptual paradigms to enrich explanatory scope. In landscape ecology, combining the theories of island biogeography, metapopulation dynamics, and habitat connectivity provides a more nuanced understanding of species dispersal and persistence in fragmented habitats. Rather than treating these theories as mutually exclusive, triangulation positions them as interdependent lenses through which ecological complexity can be refracted. Such theoretical pluralism, when reflexively maintained, prevents reductionism and sustains ecology’s interpretive openness.

Triangulated ecological applications: Triangulation’s epistemic force is most visible in its practical applications across ecological subfields. In biodiversity monitoring, triangulated approaches combine traditional field surveys with novel techniques like environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding and automated acoustic sensors (Table 6). These multiple data streams compensate for each other’s weaknesses as eDNA captures cryptic aquatic taxa, acoustic sensors monitor elusive nocturnal species, while visual transects provide ground validation. Together, they construct a multidimensional portrait of biodiversity distribution, enhancing both spatial and temporal resolution39. In ecosystem service valuation, triangulation reconciles the biophysical quantification of ecological functions with socio-economic and cultural valuations. For example, in mangrove restoration studies, remote-sensing-based carbon stock estimates are juxtaposed with community interviews on subsistence fisheries and wood harvesting. This integration balances ecological metrics with lived dependencies, generating a valuation framework that is both scientifically rigorous and socially equitable. Such triangulated valuations challenge conventional economic models that often privilege monetary measures over cultural or subsistence values.

Triangulation also underpins climate change research, particularly in impact assessment and adaptation planning. Climate models, which often operate at coarse spatial scales, are cross-referenced with local phenological observations, dendrochronological reconstructions, and indigenous seasonal calendars. The discrepancies between model predictions and local ecological experience serve as reflexive moments, prompting scientists to recalibrate assumptions and refine projections40. This participatory triangulation produces climate insights that are context-specific, policy-relevant, and culturally grounded. In hydrology and watershed management, triangulation manifests through the integration of remote-sensed hydrological indices, ground-based flow measurements, and stakeholder observations. For instance, triangulating MODIS evapotranspiration data with community-level reports of water scarcity allows managers to detect both physical and social dimensions of hydrological stress. In turn, this integrated evidence base supports adaptive water governance that is ecologically sound and socially legitimate.

Reflexive integration and the future: The essence of triangulation lies not only in methodological convergence but also in reflexive divergence or the recognition that ecological knowledge advances through contradiction and synthesis. When multiple data streams disagree, this divergence signals not error but epistemic opportunity. It provokes scientists to re-examine scale mismatches, methodological assumptions, or overlooked variables. In this sense, triangulation embodies a reflexive ecology, one that continuously redefines its truths through iterative learning loops12. Reflexive integration becomes especially vital in adaptive ecosystem management, where evidence evolves alongside ecological change. In community-based forest restoration, for example, triangulated monitoring combines satellite-detected canopy regrowth, field-based species inventories, and community storytelling about forest health. Divergences among these perspectives catalyse dialogue and learning, fostering adaptive management that is locally owned and scientifically robust. Such iterative cycles of feedback and recalibration exemplify what Funtowicz and Ravetz41 describe as post-normal ecology, where uncertainty is not eliminated but embraced as a productive force for deeper understanding.

Looking forward, the digital transformation of ecology promises to elevate triangulation into an algorithmic domain. Machine learning now enables the fusion of multispectral remote sensing, sensor networks, and participatory datasets into integrated ecological intelligence systems. However, this transition introduces new epistemic and ethical challenges: algorithmic bias, data sovereignty, and the risk of privileging computational authority over human insight. Therefore, future triangulated ecology must sustain its reflexive balance by melding the computational precision of artificial intelligence with the contextual empathy of human ecological experience.

CHALLENGES AND INTEGRATIVE PATHWAYS IN ECOLOGICAL TRIANGULATION

The application of triangulation in ecological research brings both methodological promise and philosophical complexity. On the one hand, triangulation allows researchers to corroborate, complement, and contextualise ecological findings across methods and scales. On the other hand, it exposes deep epistemic tensions between realism and constructivism, convergence and pluralism, precision and inclusivity. Understanding these tensions is vital if triangulation is to move beyond a rhetorical ideal into a practical epistemic framework for ecology. This section therefore, merges discussion of the principal challenges and the emerging integrative pathways that address them, revealing how methodological rigour, epistemic pluralism, and ethical reflexivity must work together for triangulation to flourish.

Methodological, epistemological, and practical barriers: At the methodological level, ecological triangulation frequently struggles with the assumption of independence among evidence streams. True independence is rare because ecological data are often interdependent by design: remote-sensing indices rely on ground-based calibration data; local ecological knowledge is sometimes elicited by the same field researchers who conduct biophysical surveys; and models may incorporate observational datasets that are later used to validate them. This circularity, though unintended, creates pseudo-convergence, which is an illusion of corroboration rather than independent verification. Compounding this are scale mismatches between methods. Satellite imagery may operate on kilometre-scale pixels, while field sampling captures species dynamics within square-metre plots. Interviews and ethnographic methods, in turn, deal with seasonal or multi-year temporalities. Integrating findings across these spatial and temporal frames requires careful reconciliation; otherwise, divergence may reflect methodological artefacts rather than ecological reality. As Manheim42 notes, connectivity and process scales in ecosystems rarely align neatly with human measurement systems, making the act of triangulation as much an art as a science.

Data comparability is another persistent constraint. Quantitative datasets are governed by strict protocols and metadata standards, whereas qualitative and participatory data often emerge from context-specific engagements that resist standardisation. Merging them demands interpretive labour (translation, coding, and theoretical framing) that goes far beyond technical data fusion. Consequently, poorly planned

triangulation risks producing a patchwork of disconnected findings rather than an integrated synthesis. At a deeper epistemological level, the assumption that all valid methods converge on a single ecological “truth” has been widely critiqued. Ecology now recognises multiple ontologies: physical, biological, and social worlds that may each possess independent but interacting realities 12. A fisher’s account of declining catch, a remote-sensed chlorophyll estimate, and a trophic-model output may all be valid yet incommensurable. Forcing convergence may erase the pluralism that makes ecological knowledge resilient. Campbell et al.43 warned that when researchers focus too much on making methods agree, they create a problem they called triangulation-strangulation, and in the process, they risk losing creativity and openness in interpretation.

Institutional barriers also deepen these epistemic tensions. Mixed-method ecological research requires significant time, funding, and collaboration across disciplines, as well as sustained engagement with local communities. Yet, funding timelines rarely support such long-term, complex work. In addition, peer-review and academic reward systems tend to favor neat, quantitative results over diverse or uncertain findings. Consequently, these structures discourage the practice of genuine triangulation. Furthermore, the ethical and political dimensions make these challenges even more complex. Triangulation often brings together different knowledge holders such as scientists, Indigenous peoples, local communities, and policymakers, but their insights are rarely valued equally. Consequently, when data from technologies such as satellite imagery are seen as more rigorous than experiential or indigenous knowledge, this hierarchy reproduces colonial patterns of knowing. Hence, without careful reflection, triangulation can unintentionally reinforce the same inequalities it seeks to overcome.

Integrative pathways: Despite these challenges, triangulation remains indispensable for grappling with ecological complexity. Its success depends on integrative pathways that blend careful design, institutional scaffolding, and ethical reflexivity. First, design integration must occur at the inception of a study, not as an afterthought. Ecologists should specify how each method contributes to the research question, how scales will be harmonised, and how integration will be analytically achieved. Turner et al.44 emphasise that weighting and temporal alignment of datasets should be explicitly planned rather than improvised during analysis. Pilot integration involving small-scale testing of data-fusion protocols or joint interpretation sessions helps detect scale mismatches and interpretive inconsistencies early. Teams themselves also function as instruments of triangulation. Investigator triangulation entails bringing together ecologists, social scientists, and community experts to create epistemic redundancy and diversity that strengthen interpretation. Each participant’s methodological reflexivity counters blind spots in others. In addition, joint training sessions, inter-disciplinary calibration of field instruments, and co-authored protocols ensure coherence without erasing disciplinary integrity.

Second, institutional support is essential. Triangulation cannot flourish in systems that prioritize narrow disciplinary work and quick results over collaboration and depth. Funding agencies and universities must design support systems that acknowledge the real costs of pluralism (time, translation, and trust-building), while multi-year grants that connect academic researchers with local institutions, government bodies, and civil-society partners can help build lasting infrastructures for genuine triangulation. Likewise, publication outlets should evolve to value mixed-method studies that present divergence or partial alignment as meaningful outcomes, rather than treating convergence as the only sign of success. Capacity building is also central to making triangulation a lasting practice. Ecologists trained in quantitative modelling need opportunities to learn qualitative and participatory methods, while social scientists working in ecological contexts benefit from foundational ecological literacy. Likewise, Indigenous and community partners should have access to technologies and data platforms that enable their knowledge to be shared and applied equitably, rather than extracted. Timmons and Weil45 emphasized that methods and theory in socio-ecological research must be reoriented through collaborative learning and cross-boundary fluency, a principle that lies at the core of truly integrative triangulation.

|

Third, ethical reflexivity provides the moral foundation for triangulation. It calls for ongoing reflection on whose voices are included, how interpretations are made, and how findings are used. Reflexivity also means being transparent about disagreement or inconsistency. For instance, if remote-sensing data indicate vegetation recovery while local communities report soil decline, this difference should be highlighted rather than hidden. Such divergence can uncover new ecological dynamics, for example, improved canopy cover may mask nutrient loss, making it an opportunity for deeper understanding. Jager et al.46 asserted that participatory environmental governance achieves stronger outcomes when stakeholders help shape the evidence base; triangulation can serve this participatory function when designed inclusively. Ethical triangulation, therefore, depends on the co-production of knowledge. Rather than treating Indigenous ecological knowledge as an add-on, integrative research approaches position it as an equal partner. Co-production starts with shared problem framing, continues through data gathering and analysis, and extends to dissemination, ensuring that findings are communicated in culturally relevant and policy-useful ways. This inclusive model not only enhances the legitimacy of ecological research but also broadens its interpretive reach.

Reflexive integrative model: Synthesizing the above pathways yields a dynamic model of integrative triangulation (Fig. 6). The model portrays research as a recursive cycle: Problem framing, method selection, data collection, integration and reflection, and knowledge mobilisation, all embedded within iterative feedback loops that involve stakeholders at each phase. In this framework, triangulation functions less as a validation tool and more as a reflexive learning system. The aim is not necessarily the convergence of all evidence but meaningful integration that honours divergence and uncertainty. The process begins with co-framing of research questions to ensure alignment between ecological, social, and cultural dimensions. Method selection follows, guided by complementarity rather than redundancy. During data collection, constant comparison across methods fosters adaptive calibration. Integration occurs through reflexive synthesis workshops or joint analyses where stakeholders collectively interpret data. The final phase, knowledge mobilisation, disseminates results back into management and policy contexts closing the loop and stimulating new cycles of inquiry. This iterative cycle resonates with the notion of ecology as a post-normal science, where uncertainty, value conflicts, and complexity are intrinsic. Triangulation here becomes a governance instrument organising dialogue between evidence systems rather than enforcing epistemic uniformity.

Toward institutionalisation and future prospects: The effectiveness of triangulation ultimately depends on the broader research ecosystem. Achieving this requires structural transformation in four key areas, namely: Funding, training, publishing, and policy connection. Funding bodies must actively support mixed-method research that integrates qualitative, quantitative, and participatory approaches. Training programs should cultivate epistemic humility by helping ecologists engage with and value different knowledge systems and methodological traditions. Journals, meanwhile, need to prioritise transparency in how integration is achieved and welcome publications that openly discuss divergence as part of the research process. Policy institutions should also begin to require triangulated evidence in environmental decision-making, recognising that such plural evidence strengthens the legitimacy and reliability of ecological claims.

Emerging technologies bring both promise and risk. Machine learning, sensor networks, and environmental DNA analysis now offer unprecedented volumes of ecological data, yet they can also deepen the gap between technological and experiential knowledge. To remain inclusive and contextually grounded, these digital tools must be triangulated with field-based observations and local narratives, ensuring that algorithmic insights are interpreted within ecological and social realities. Integrative triangulation therefore, provides a pathway for this balance linking technological precision with human understanding. Finally, the globalisation of ecology calls for transboundary triangulation that entails the integration of data and knowledge across ecosystems, nations, and cultures. Collaborative observatories, citizen-science initiatives, and regional knowledge networks can help realise this vision, advancing what may be called planetary triangulation, a plural, co-produced ecological epistemology responsive to both planetary processes and local lived realities.

CONCLUSION

Triangulation provides a vital approach to addressing the epistemic and practical challenges of studying complex ecological systems. By integrating empirical, interpretive, and participatory perspectives, it strengthens inferences, broadens interpretive scope, and embeds ethical accountability within ecological research. However, its transformative potential depends on institutional support. Current funding structures, publication norms, and performance metrics often prioritize methodological conformity and rapid outputs over pluralism and reflexivity. Embedding triangulation within ecological science requires sustained investment in integrative research infrastructures, including multi-year funding programs, interdisciplinary training, and publication venues that promote transparency about methodological diversity.

Ethical reflexivity remains essential, ensuring that diverse epistemologies, particularly Indigenous and experiential knowledge, are engaged as co-equal contributors to ecological understanding. Emerging technologies, such as environmental DNA, remote sensing, and machine learning, offer unprecedented data opportunities but risk exacerbating epistemic imbalances if detached from local contexts. Triangulation helps anchor these tools in field-based and community knowledge, maintaining ecological relevance and social legitimacy. At a planetary scale, transboundary collaborations, through global observatories, citizen-science networks, and cross-regional partnerships, enable what may be termed planetary triangulation: an integrative ecological inquiry linking global data infrastructures with situated human experience.

Ultimately, triangulation is not merely a methodological safeguard but an epistemic ethos for twenty-first-century ecology, valuing diversity, reflexivity, and co-production as the foundation of robust and equitable environmental knowledge.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Triangulation enhances ecological research by integrating empirical, interpretive, and participatory perspectives, ensuring rigor, ethical accountability, and inclusivity. By engaging Indigenous and experiential knowledge alongside emerging technologies, it maintains ecological relevance and social legitimacy. Institutional support, interdisciplinary training, and long-term funding are essential. At a global scale, planetary triangulation links large-scale data with local knowledge, providing a framework for equitable, robust, and actionable environmental understanding.

REFERENCES

- Adediran, E., 2024. Complexity theory; unraveling the fabric of intricacy. SSRN J.

- Swargiary, K., 2024. Research Methodologies: Evolution, Practice, and Prospects. ERA, US, Texas, USA, Pages: 125.

- Caggiano, H. and E.U. Weber, 2023. Advances in qualitative methods in environmental research. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour., 48: 793-811.

- Dobson, A.D.M., E.J. Milner-Gulland, N.J. Aebischer, C.M. Beale and R. Brozovic et al., 2020. Making messy data work for conservation. One Earth, 2: 455-465.

- Bruce, T., Z. Amir, B.L. Allen, B.F. Alting and M. Amos et al., 2025. Large-scale and long-term wildlife research and monitoring using camera traps: A continental synthesis. Biol. Rev., 100: 530-555.

- Lindenmayer, D.B. and G.E. Likens, 2018. Effective Ecological Monitoring. 2nd Edn., CSIRO Publishing, Clayton, Victoria, Australia, ISBN: 9781486308934, Pages: 212.

- Worden, M.A., T.E. Bilir, A.A. Bloom, J. Fang and L.P. Klinek et al., 2025. Combining observations and models: A review of the CARDAMOM framework for data-constrained terrestrial ecosystem modeling. Global Change Biol., 31.

- Sanborn, T. and J. Jung, 2021. Intersecting social science and conservation. Front. Mar. Sci., 8.

- Jacob, D.E., I.D. Jacob, K.M. Udofia, K.S. Daniel, S.I. Okweche, E.A. Dan and P.U. Evansly, 2024. Leveraging blockchain and AI for transparent and equitable protected area and recreation co-management. Community Ecol., 2.

- Miller, R.W., 1988. Fact and Method: Explanation, Confirmation and Reality in the Natural and the Social Sciences. Princeton University Press, New Jersey, USA, ISBN: 9780691020457, Pages: 628.

- Denzin, N.K., 2017. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. 1st Edn., Routledge, New York, ISBN: 9781315134543, Pages: 379.

- Vogl, S., E.M. Schmidt and U. Zartler, 2019. Triangulating perspectives: Ontology and epistemology in the analysis of qualitative multiple perspective interviews. Int. J. Social Res. Methodol., 22: 611-624.

- McGowan, J., R. Weary, L. Carriere, E.T. Game, J.L. Smith, M. Garvey and H.P. Possingham, 2020. Prioritizing debt conversion opportunities for marine conservation. Conserv. Biol., 34: 1065-1075.

- Riva, F., C. Graco-Roza, G.N. Daskalova, E.J. Hudgins and J.M.M. Lewthwaite et al., 2023. Toward a cohesive understanding of ecological complexity. Sci. Adv., 9.

- Lazurko, A., L.J. Haider, T. Hertz, S. West and D.D.P. McCarthy, 2024. Operationalizing ambiguity in sustainability science: Embracing the elephant in the room. Sustainability Sci., 19: 595-614.

- Elves-Powell, J., J. Dolan, S.M. Durant, H. Lee, J.D.C. Linnell, S.T. Turvey and J.C. Axmacher, 2024. Integrating local ecological knowledge and remote sensing reveals patterns and drivers of forest cover change: North Korea as a case study. Reg. Environ. Change, 24.

- Trinchini, L. and R. Baggio, 2023. Digital sustainability: Ethics, epistemology, complexity and modelling. First Monday, 28.

- >Dawadi, S., S. Shrestha and R.A. Giri, 2021. Mixed-methods research: A discussion on its types, challenges, and criticisms. J. Pract. Stud. Educ., 2: 25-36.

- Jacob, D.E., I.U. Nеlson and S.C. Izah, 2024. Indigenous Water Management Strategies in the Global South. In: Water Crises and Sustainable Management in the Global South, Izah, S.C., M.C. Ogwu, A. Loukas and H. Hamidifar (Eds.), Springer Nature, Singapore, ISBN: 978-981-97-4966-9, pp: 487-525.

- Kimbowa, G., J. Buyinza, J.M. Gathenya and C. Muthuri, 2024. Learning from local knowledge on changes in tree-cover and water availability: The case of the contested agroforested landscape of the Mt. Elgon Water Tower, Uganda. Front. Water, 6.

- Dronova, I., C. Kislik, Z. Dinh and M. Kelly, 2021. A review of unoccupied aerial vehicle use in wetland applications: Emerging opportunities in approach, technology, and data. Drones, 5.

- Pullens, J.W.M., M. Bagnara, R.S. González, D. Gianelle and M. Sottocornola et al., 2017. The NUCOMBog R package for simulating vegetation, water, carbon and nitrogen dynamics in peatlands. Ecol. Inf., 40: 35-39.

- Berkeley, B., 2022. Evaluating complementarity in sociological worldviews and in sociological methods of data collection. Open Access Lib. J., 9.

- Jacob, D.E., S.C. Izah, I.U. Nelson and K.S. Daniel, 2023. Indigenous Knowledge and Phytochemistry: Deciphering the Healing Power of Herbal Medicine. In: Herbal Medicine Phytochemistry: Applications and Trends, Izah, S.C., M.C. Ogwu and M. Akram (Eds.), Springer International Publishing, New York, ISBN: 978-3-031-21973-3, pp: 1-53.

- Berkes, F., 2017. Context of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. In: Sacred Ecology, Berkes, F. (Ed.), Routledge, New York, ISBN: 9781315114644.

- Karcher, K., J. McCuaig and S. King-Hill, 2024. (Self-) reflection / reflexivity in sensitive, qualitative research: A scoping review. Int. J. Qual. Methods, 23.

- Block, K., 2024. Epistemic caring: An ethical approach for the co-constitution of knowledge in participatory research practice. Social Epistemology.

- Molnár, Z. and D. Babai, 2021. Inviting ecologists to delve deeper into traditional ecological knowledge. Trends Ecol. E, 36: 679-690.

- Motohka, T., M. Shimada, Y. Uryu and B. Setiabudi, 2014. Using time series PALSAR gamma nought mosaics for automatic detection of tropical deforestation: A test study in Riau, Indonesia. Remote Sens. Environ., 155: 79-88.

- Bloor, D., 2019. Relativism and Antinomianism. In: The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Relativism, Kusch, M. (Ed.), Routledge, New York, ISBN: 9781351052306.

- Dion, A., A. Carini-Gutierrez, V. Jimenez, Amal Ben Ameur, E. Robert, L. Joseph and N. Andersson, 2021. Weight of Evidence: Participatory methods and bayesian updating to contextualize evidence synthesis in stakeholders’ knowledge. J. Mixed Methods Res., 16: 281-306.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S., 2017. Decolonising research methodology must include undoing its dirty history. J. Public Adm., 52.

- Vivek, R., 2024. A comprehensive review of environmental triangulation in qualitative research: Methodologies, applications, and implications. J. Eur. Econ., 22: 517-532.

- Ogunkan, D.V. and O.P. Akinpelu, 2025. Methodology mayhem in urban planning research: A call for methodological triangulation. Qual. Quant.

- Andrada, G., 2021. Epistemic Complementarity: Steps to a Second Wave Extended Epistemology. In: The Mind-Technology Problem: Investigating Minds, Selves and 21st Century Artefacts, Clowes, R.W., K. Gärtner and I. Hipólito (Eds.), Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, ISBN: 978-3-030-72644-7, pp: 253-274.

- Harrison, L.E., J.A. Flegg, R. Tobin, I.N.D. Lubis and R. Noviyanti et al., 2024. A multi-criteria framework for disease surveillance site selection: Case study forPlasmodium knowlesi malaria in Indonesia. R. Soc. Open Sci., 11.

- Peterson, E.A., C.E. Stuart, S.J. Pittman, C.E. Benkwitt and N.A.J. Graham et al., 2024. Graph-theoretic modeling reveals connectivity hotspots for herbivorous reef fishes in a restored tropical island system. Landscape Ecol., 39.

- Flick, U., 2018. Triangulation in Data Collection. In: The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection, Flick, U. (Ed.), Sage Publications Ltd., New York, ISBN: 9781526416063.

- Bibi, M., S. Hassan, T. Noor, M. Waheed and A. Bilal et al., 2025. Structural and biochemical insights into CRISPR-cas nucleases for therapeutic genome editing. Haya: Saudi J. Life Sci., 10: 362-375.

- Niang, K., J. Blinkhorn, M.D. Bateman and C.A. Kiahtipes, 2023. Longstanding behavioural stability in West Africa extends to the Middle Pleistocene at Bargny, Coastal Senegal. Nat. Ecol. E, 7: 1141-1151.

- Funtowicz, S. and J. Ravetz, 2020. Post-Normal Science: How Does it Resonate with the World of Today? In: Science for Policy Handbook, Šucha, V. and M. Sienkiewicz (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, ISBN: 978-0-12-822596-7, pp: 14-18.

- Manheim, D., 2023. Building less-flawed metrics: Understanding and creating better measurement and incentive systems. Patterns, 4.

- Campbell, R., R. Goodman-Williams, H. Feeney and G. Fehler-Cabral, 2018. Assessing triangulation across methodologies, methods, and stakeholder groups: The joys, woes, and politics of interpreting convergent and divergent data. Am. J. Eval., 41: 125-144.

- Turner, B.M., M. Steyvers, E.C. Merkle, D.V. Budescu and T.S. Wallsten, 2014. Forecast aggregation via recalibration. Mach. Learn., 95: 261-289.

- Timmons, D.S. and B. Weil, 2022. A cost-minimizing approach to eliminating the primary sources of greenhouse gas emissions at institutions of higher education. Int. J. Sustainability Higher Educ., 23: 604-621.

- Jager, N.W., J. Newig, E. Challies and E. Kochskämper, 2020. Pathways to implementation: Evidence on how participation in environmental governance impacts on environmental outcomes. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory, 30: 383-399.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Jacob,

D.E., Jacob,

I.D., Daniel,

K.S. (2026). Triangulation in Ecological Research: Epistemological Roots, Field Realities, and Integrative Pathways. Trends in Environmental Sciences, 2(1), 50-68. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.50.68

ACS Style

Jacob,

D.E.; Jacob,

I.D.; Daniel,

K.S. Triangulation in Ecological Research: Epistemological Roots, Field Realities, and Integrative Pathways. Trends Env. Sci 2026, 2, 50-68. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.50.68

AMA Style

Jacob

DE, Jacob

ID, Daniel

KS. Triangulation in Ecological Research: Epistemological Roots, Field Realities, and Integrative Pathways. Trends in Environmental Sciences. 2026; 2(1): 50-68. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.50.68

Chicago/Turabian Style

Jacob, D., E., I. D. Jacob, and K. S. Daniel.

2026. "Triangulation in Ecological Research: Epistemological Roots, Field Realities, and Integrative Pathways" Trends in Environmental Sciences 2, no. 1: 50-68. https://doi.org/10.21124/tes.2026.50.68

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.